CAFE IMPORTS + BRAZIL

Our relationship with Brazil can fairly be called more of a love affair: There’s a lot of romance for us in this big, beautiful coffee country, but we are also attracted to the challenges and are always actively seeking new ways to discover, develop, and source quality coffees from our main export partners. We travel to several primary coffee regions a few times every year in the interest of inspecting quality, maintaining relationships, introducing our roaster partners to the magic (and sometimes mayhem) or Brazilian production, and seeking new and “undiscovered” corners where specialty coffee might flourish.

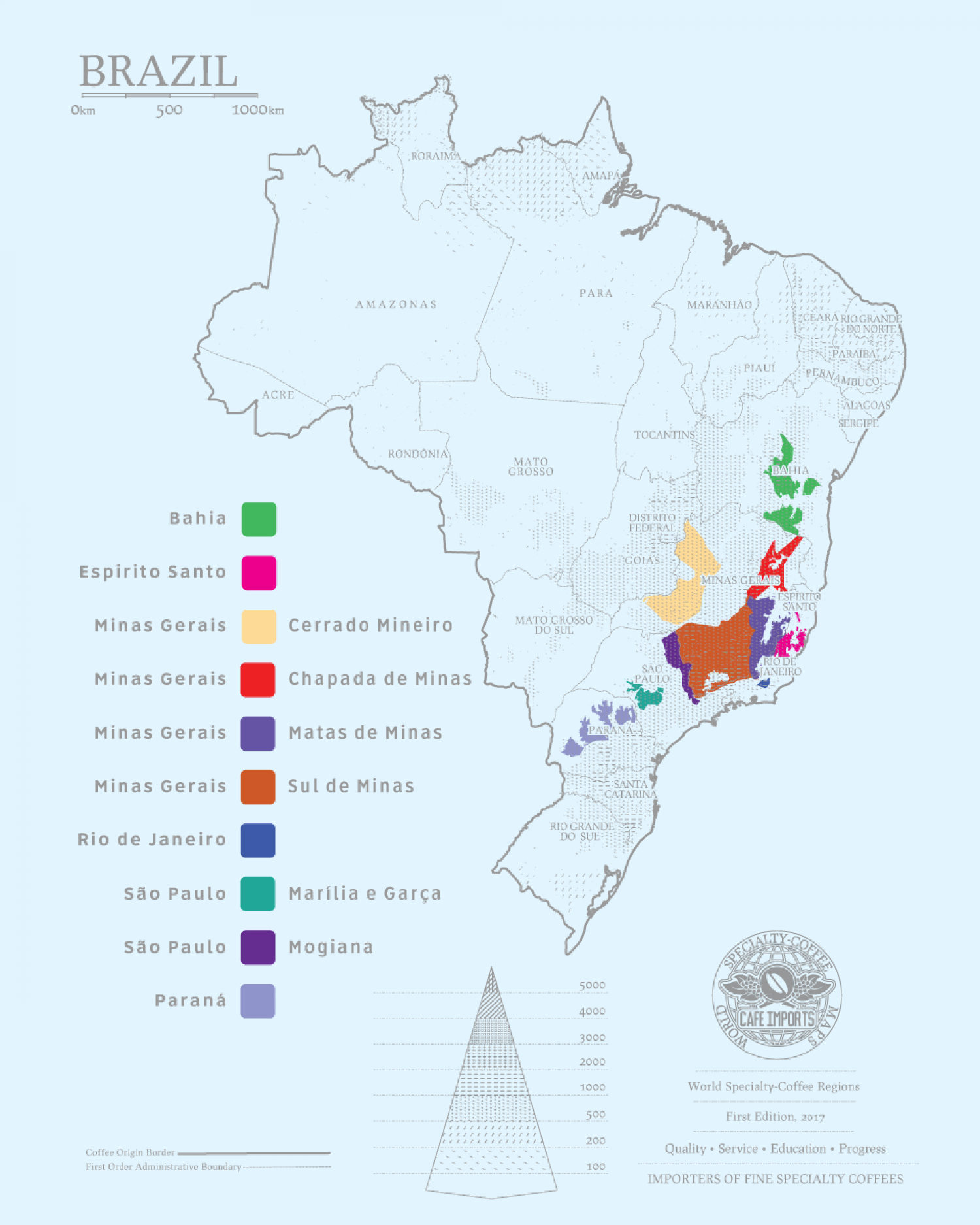

In fact, Brazilian coffee was what started Cafe Imports to begin with: Founder and partner Andrew Miller imported his first container with a Brazilian friend in 1994, bringing in a coffee that would be the genesis of our "signature" Brazil offering, Serra Negra. Since then, countless full-container loads from Carmo de Minas and Mogiana have come through our warehouse, and the quality and diversity that we've seen from various regions and microregions (and micro-microregions!) have inspired the development of microlot programs with some of the country's most innovative producers. In short, we're still madly in love.

Today, we are building upon our existing relationships and introducing new ones every year. With its efficient production and massive yields, Brazil is often overlooked as a potential source for microlot coffees: Carmo Best Cup should bring to the fore some of the producers who are focused on putting out smaller quantities of hyperfocused, high-scoring, practically mind-bendingly good coffees from around the region, and we look forward to that level of quality becoming more of a norm than an exception when “Brazilian coffees” comes to a roaster’s mind.

HISTORY

It’s hard to imagine the “beginnings” of coffee in Brazil, as the two things have become so synonymous. The first coffee plants were reportedly brought in the relatively early 18th century, spreading from the northern state of Pará in 1727 all the way down to Rio de Janerio within 50 years. Initially, coffee was grown almost exclusively for domestic consumption by European colonists, but as demand for coffee began to increase in United States and on the European continent in the early-mid 19th century, coffee supplies elsewhere in the world started to decline: Major outbreaks of coffee-leaf rust practically decimated the coffee-growing powerhouses of Java and Ceylon, creating an opening for the burgeoning coffee industry in Central and South America. Brazil’s size and the variety of its landscapes and microclimates showed incredible production potential, and its proximity to the United States made it an obvious and convenient export-import partner for the Western market.

In 1820, Brazil was already producing 30 percent of the world’s coffee supply, but by 1920, it accounted for 80 percent of the global total.

Since the 19th century, the weather in Brazil has been one of the liveliest topics of discussion among traders and brokers, and a major deciding factor in the global market trends and pricing that affect the coffee-commodity market. Incidents of frost and heavy rains have caused coffee yields to wax and wane over the past few decades, but the country is holding strong as one of the two largest coffee producers annually, along with Colombia.

One of the other interesting things Brazil has contributed to coffee worldwide is the number of varieties, mutant-hybrids, and cultivars that have sprung from here, either spontaneously or by laboratory creation. Caturra (a dwarf mutation of Bourbon variety), Maragogype (an oversize Typica derivative), and Mundo Novo (a Bourbon-Typica that is also a parent plant of Catuai, developed by Brazilian agro-scientists) are only a few of the seemingly countless coffee types that originated in Brazil and, now, spread among coffee-growing countries everywhere.

PICKING AND PROCESSING

In order to maintain production at the scale and scope for which Brazil is famous, the national industry has adopted specific and to some degree innovative means to achieve both picking and processing in the most highly efficient and organized manner possible, and the structure of the average farm or estate is designed around utilizing these systems and maximizing the yield potential per hectare.

Strip picking, either mechanically or by hand, is one of the efficiencies that is commonly found on farms of all sizes in Brazil: Instead of the labor-intensive selective picking typical to the rest of the coffee-producing Americas, coffee is picked less discriminately cherry-by-cherry, but rather sorted by ripeness after more general collection. In some instances, pickers use towels, tarps, and/or heavy gloves to simply strip cherries from the branches at the peak of the harvest, collecting them in baskets, barrels, or in sacks and cloth bags. Elsewhere, on much larger farms, coffee plants are arranged in rows more akin to corn fields in Iowa than the forest-like environment of Ethiopia or Colombia: Mechanical pickers will pass through and shake the trees, which loosens the riper cherries and allows them to be collected for sorting and processing.

While these methods raise some criticism from specialty-coffee circles, they are what have allowed for Brazil to maintain its position as a tremendous source for volume, and in many cases also imparts some of what is considered the classic Brazil profile that is richer in chocolate, nut, and pulpy coffee-cherry notes.

Speaking of pulpy notes, Brazil's’ post-harvest processing is also somewhat unique, and has been adapted largely in response to a combination of productivity, climate, and desired profile: Pulped Natural and Natural processing still dominates the industry here: Pulped Natural coffees are depulped and allowed to dry with their mucilage still intact; while Naturals are typically either dried on the trees before harvesting (called Boya), or picked and laid out on patios in order to finish drying before being hulled. Both processes tend to lend the coffees a nutty creaminess that has a more tempered fruit tone than the bright and acidic Washed or even Honey coffees we see elsewhere from Mesoamerica. The Natural coffees Cafe Imports sources from Brazil are “special prep,” picked ripe and dried on patios to spec.