Non-Linear Coffee Loops

I recently re-read a book on nonlinear dynamics as applied to Euro history over roughly the last thousand years. Basic to this approach is that evolutionary changes are not given as necessary, much less as inevitable, much-much less as advancement, improvement or progress. Evolution as change is affirmed, and radically so. What is denied is any purposiveness or teleology to that change. The various forces or flows that make up these systems change by gravitating around patterns that emerge within the flows themselves, whether via the introduction of a catalyst or the developing of interactions between the already present flows. The focus is on the internal morphogenetic capabilities of matter-energy, with matter-energy being a universally inclusive category. The emergence of a small pattern acts on the existing flows of matter and energy via turbulence, accumulation, restriction, rerouting, digestion, etc. Formed in a certain way, these small patterns continue to accumulate and build, changing the flows that they pull from (and the interactions of those flows) while simultaneously being changed themselves as they grow. At a certain point a stable state may occur. When this happens, energy and matter flows normalize and change decelerates. History generally focuses on the stable states, which are easier to see for being slower and more simply organized. From this point of view, privileging change as progress is just the winner’s tale, while romanticising the past (regardless of political bent) is the poetry of 20 year olds. Neither has much basis (apart from the catalytic or social accumulatory functions that either may perform) in reality.

Ten years ago Sumatran coffee tasted like moldy carpet and forest floor (it was supposed to). More recently, cleaner, higher acid and sugar content coffees (*defects do not reduce cup quality only by the addition of defective qualities; because of regular dosing they also count as subtractions of non-defective qualities: if you begin with a 20g dose of quaker free coffee and then add 2g of quaker, practically speaking, you don’t end up with 22g because with respect to dosing you must remove 2g of the original clean lot. Tasted coffee is always dosed coffee and in our example the addition of quaker requires the displacement of clean in order to maintain uniform dosing. From the other side, the removal of defects assumes replacement with defect free beans) have been offered up by Sumatra- very much to mixed review. Is this an advance? It is a change. The relatively tepid response (it doesn’t taste like a Sumatra) argues for the non-inevitability of change as progress-or progress as change. That was ten years ago. Ten days ago Sumatran coffee tasted like moldy carpet and forest floor… and it tasted like roasted veg, grapefruit, citrus, savory-floral, butter, raisin, fig, goji, and acai. It is only in the most hierarchical and anti-market (7-8-9-10) systems that an emergent stable state replaces its predecessor. More commonly successive or bifurcated stable states exist beside one another, interacting and further influencing each other’s evolution, engaged in some level of meshwork dynamic. If one fades from the world stage by the other’s influence, it is not without having exerted a defining force on the one that remains- itself no longer absolutely identifiable with its emergent state.

More on this as we continue.

Importing Sumatran coffee, we see clearly that the drive for ever bourgier cups (ever bigger, ever fruit forwarder, ever easier, ever more similar) does not by necessity eliminate the appreciation of less consistent, rougher, more rustic and even more defective profiles. We see further that the assessment of les nouveaux bourgies Sumis is fully dependent on the more classic profiles for structure and definition. If I tasted a wet-hulled Sumatran coffee that was so “clean” that I couldn’t tell it from an El Sal, at least as our current standards rate, this would be a limiting factor on the score of that cup. Even the cleanest Sumatran coffee needs to maintain a certain level of process and origin integrity. It should not defy the process, the origin, but should exemplify it. As suggested, these newer cups are also exerting some influence on the classic profiles. If the bar is changing on the upper ends, the process typical profile- in our case the Tiger- is responding. We’re not interested in moldy carpet. We’re looking for clean earth, forest floor/autumnal leaves, fresh compost and freshly cut cedar, and we’re finding it.

A couple of notes are in order here discussing the types of language used to describe Sumatran coffees (and non-washed process coffees generally). As I’ve written elsewhere, when we created our process specific standards we made a central focus of not being washed-centric in the scaling. There are two big traps of discourse that I would like to point out with this in mind: apologetics and cloaking. Apologetics is a type of discourse systematically defending a position, generally against charges of irrationality. Of course, irrationality is therefore often implied by the presence of apologetics. It is here that apologetics slips into the subtle and unintended treachery known as blaming with faint praise. Along these lines, cloaking is a type of discourse systematically obscuring a position against charges generally. Of course, all variety of charges are implied by the use of cloaking. It is here that cloaking can slip into one of those increasingly complex regresses also known as a webs of lies.

There are thick layers of both apologetics and cloaking draped around Sumatran coffee. It’s built into the brand. Bluntly, “Sumatran Coffee” built a brand of being defective. Kudos. Like going to a restaurant where the service is bad on purpose, or buying farm and fleet wardrobes from boutiques, Sumatran coffee really should hold a stronger appeal to the irony addled and misused taste-couture of our contemporary culture. I know. Apologies. It’s just that, similar to Neil DG Tyson, whether or not you believe that standard Sumatran coffees are defective does not in any way impact whether or not they are actually riddled with defects.

We can take “earthy” as an example. Earthy is far more general than descriptive, as different plots of earth have very different aromatics (and if you’re a gardener or mudpie maker, very different flavors). In washed coffees “earthy” carries sufficient resolution as a descriptor of something undesirable. In wet hulled coffees, where that resolution has rarely been refined, a wide variety of coffee flavor profiles have been lost to “earthy”.

Earthy can serve as both cloak- for defects, and as apology- for discomfort with a non-washed profile. But what if you use it at face value? What if you dig in, as it were? Earthy can then serve as a gateway to expanding the palate and its fluency with a diverse group of flavors. The importance is this: Some of the coffees that we’re now seeing emerge within this same Sumatran brand are dropping the defects- but not the character.

So where are we going here? I’ve written a few times before, on this blog and elsewhere. If you’re familiar with all that, you’ll recognize that it takes the patience of a Barista or Roast Magazine editor to rein these things in. Rest assured, there’s no editor here.

Jason and I took a trip to Sumatra last November. The goal was to see something of how things operated on the ground in Sumatran coffee. The stories surrounding how Sumatran coffee is produced and how its profiles are achieved are varied to say the least. We had great success with a cherry selected micro-lot last year, and so knew something of what could be done. Our questions: Can we do more of that? Is it be possible to raise the bar also on our Tigers and FTOs? What exactly would that take? What would it even look (and taste) like?

Speaking to the micro-lots, at breakfast in a small Aceh hotel one morning I ran into a buyer from Japan that I’d met a couple times through Cup of Excellence competitions. He asked me what I was doing in Aceh (a fair question, given the ends of the earth feel that this particular town had, and C.I.’s predilection for the sort of coffee one might not expect to find there), “looking for micro-lots?” Shrugging, I said “Good question.” We both laughed and I went to join Jason for a breakfast of spicy rice and fried eggs.

The process of acquiring Sumatran coffee is convoluted in large part by the presence of collectors. Collectors are people who buy coffee at various stages of process from farmers (generally cherry or pulped full moisture), continue that processing to some extent, and then deliver the coffee to Coops or exporters, who finish the processing and export the coffee. When you visit with a Coop, as you would anywhere, you can speak with farmers and visit farms, you can learn about Coop organization, varieties, yields, pests, and etc. Still, the absence of the collector at these meetings severely limits their usefulness. This is because without the collector, the Coop has no say over what gets delivered, and on the other side, the farmer has no say over with what or to whom their coffee is delivered.

We needed to talk to some collectors, but I’m ahead of myself.

One of the challenges and reasons for our trip goes like this: when we visit other coffee producing countries, we know what we want. We don’t really know what we want from Sumatran coffee. Do we want coffees in the style of clean, washed centrals, because that’s the right way to process? Of sun dried Ethiopians or pulp natural Brazils? Wet hulling is flat wrong in so many ways. I can explain. Emphasis added.

In Sumatra, coffee is:

Harvested. So far so good, excepting the many levels of non-selectivity.

Mechanically pulped. This is mostly just the skin. Mucilage is largely left on. Coffee is stored for up to a day, frequently in sacks, and then washed. This “storing” is essentially a loosely controlled dry ferment that allows the mucilage to be washed off.

After washing it’s dried to approximately 30-35% moisture. I’ve read, and we were told, 30-40%. This is generally the point at which coffee is sold to a collector.

Dry milled. Parchment is mechanically removed while the coffee is still at 25-35% moisture. The blue-green color of many Sumatran coffees is attributed to this early hulling. Also attributable to this method are the frequently crushed, broken and subsequently infected beans present in Sumatran coffees. Green coffee fresh on the patio is soft enough to be bent between thumb and forefinger.

Patio dried. Road side dried. Tarp on ground dried.

So why not go and get them to stop it? For one, because that misses the point entirely. While the world of wine has embarked happily (successfully) on the road to homogenization, and while portions of the coffee world seem yearning to follow, this may be a point where it’s good to be so far behind.

A good question illustrating this: why would you roast anything other than Kenyan and Ethiopian coffee, maybe with a small seasonal high altitude Central or top flight Colombian? Why even look at coffees from anywhere else when you’d be so hard pressed to find anything objectively better by attributes (Sweetness? Nope. Acidity? Nope. Complexity? Nope. Transparency? Nope.) than what these origins can offer? Simply stated: because other coffees are different, unique, interesting. El Salvador can offer cups that Kenya categorically can not offer. There is a 100 point cap on most 100 point scales; there are also other, nonlinear limits. Back to Sumatra.

You may have seen our cherry ripeness cards. These handy little cards depict a gradation of coffee cherries from very green to very purple- from under to over-ripe. Three cherries

are highlighted as ideally ripe, and stamped with a reassuring thumbs up. At the first Coop we visited we pulled out the cards, mostly as a starting point for conversation. They brought us a cherry sample, essentially saying “Yes, we definitely do that”:

“All of it.” OK. Well, we’ve been drinking Sumatran coffee for a long time now and as such it’s really no more hit and miss than anything else- if you consider that hit and miss is an integral part of the coffee (see how meta I just got). This is at a good Coop, with good coffee. If this selection was the norm, then the card was lacking a certain level of applicability, rather than the other way round. We began by asking if the selection on a particular lot could be refined by maybe just eliminating the greens and yellows. The idea being to try something achievable within the given context and see what changes. If pulling greens and yellows didn’t make a noticeable difference in the cup, it wouldn’t make sense to push for even finer resolution- it would just make more work and more expense for an unknown and likely small gain. Starting small and working progressively allows us to find out- without undue expectations or stresses on either side.

On to our first farm visits (finally, it took us a couple of days and a 10 hour drive before we were on our first farm). The first thing you notice is that the farms are green. GREEN. Shade plantings are well organized, varied, and numerous. The soil is soft, a rich red-brown. Everything looks healthy. There are touches of rust here and there, but few and far between from what we saw. Everything is dripping. Coffee trees can be in all stages of production- new growth, flowers, green and ripe cherries.

The majority of trees are HdT and Catimor derived, which is to say, the majority of Sumatran coffee is HdT and Catimor. This is important. If you’ve ever enjoyed a Sumatran coffee, you’ve probably enjoyed Catimor. Locally, the common names are Tim-Tim and Ateng, respectively. It seems that there are numerous locally adapted Catimor varieties, some of which are claimed to have excellent cup qualities. More on this soon.

One of the things that makes Sumatra so interesting is that mixed in with all the HdT there are very old Typica and Ethiopian plants, as well as some Caturra and Bourbon. The question was begged: “Can you show us some Typica-Ethiopian-Caturra-Bourbon trees?” And off we’d go. Pulling up to a farm, showing us the Typica, et al. meant wading through rows and rows of Ateng. You’d get to a corner of the farm and they’d say, “This is Caturra.” Or you’d be walking along and they’d point out here and there, “This is Typica, this is Ethiopian.” Ok. “Is it possible to pick just the Typica? Just the Abyssinia?” -hesitation. The thing is, most Sumatran coffee is not picked like that. The varieties are as mixed as the ripeness, and it’s all just picked for process. The collectors ask for weight, purchase weight, process and sell weight.

If you’ve ever enjoyed a Sumatran coffee and thought, “This is Sumatran!?”, then brewed another cup and with dashed hopes realized “this is Sumatran [decrescendo].”, you’ve probably hit an Arabica seam in the lot (though not necessarily- more on this).

Anywho, bummer. We gotta talk to some collectors. There’s a whole world of random involved here, and it seems to orbit the collectors.

We left our first group of Coop visits with a simple plan in place. We would receive samples representing small lots collected from different communities within the Coop. This would allow us to see if small local differences- whether in processing, HdT%, or terroir would show up in the cup. If not, the coffees could be blended and purchased as per normal with us paying a small premium for the effort. In addition to this, we emphasized the success of the cherry selection lot, and worked out the details to build on that success.

From here we were off to Wahana estate, unique in that they are able to offer single varieties and maintain control from planting to export. We began by cupping in their lab. I can flatly state that this was one of the single most interesting cuppings I’ve ever participated in. There were washed, wet-hulled and natural processed coffees on the table (all Sumatran). There were standard regional blends and single variety lots- both Atengs and Arabicas.

This cupping isolated a lot of variables we weren’t sure we would be able to reliably isolate. A number of these coffees were what I would consider good, standard Sumatrans. The Lintong and the Mandheling regional coffees were both obviously Sumatran, and were both very distinct from one another- the Lintong was buttery, grassy, and vegetal, while the Mandheling was earthy, bell peppery and a little grapefruity/pithy. The natural coffee tasted like a cross between the big (if simpler) blueberry blushed naturals of Central America with the wilder wine and compote of our Yemeni Haraaz.

The top three coffees were a Jantung- this is a Typica; a Longberry- this is thought to be an adapted relative of Ethiopia’s Harrar Longberry; and another called Andongsari. The first two are essentially what we came looking for. Both stood out on the table. The surprise was the Andongsari. Selected from a Colombian Catimor (read: highly selected and carefully back-crossed), this is a Catimor-Caturra-HdT cross that was released by the Indonesian Coffee and Cacao Research Institute. In the cup it tasted like what it would taste like if raisins could be raisinated (like if you made cookies, dried and ground them into a flour, and then used that cookie flour to make another batch of cookies). Very saturated (and delicious) to say the least. We’re excited to be bringing these coffees in to say even less.

More recently in our lab’s PSS cupping, both the Jantung and the Longberry stood out even more. While the Andongsari maintained it’s double-take depth, this time the profile was strictly Sumatra: roasted Serrano and Bell peppers, sweet, and very heavy bodied. The Jantung scored high with deep, savory fruit, very tangy acidity, honeydew melon, and lemon curd. The Longberry, while not topping out the Jantung’s depth and score, was probably the most interesting on the table with a full range of notes from floral tea, rose water, and citrus, to butter and roasted tomatoes.

We considered cutting our trip short at this point. What else could we see? By way of offering a bit of unsolicited advice: if you’re ever visiting a place in which everything you see is different from what you’ve seen, don’t rhetorically ask “what else could we see?”. We sort of asked that, but we also went on, if mostly out of respect for having made further appointments. The thing was that we were heading back to Coops- different Coops, but same Coop questions (remember, we’d seen those already, asked those already…). The thing was, and little did we know, that things were just getting warmed up.

We began with a meeting in the Coop office, discussing Coop things, and eating packets of Nasi Goreng- spicy, oily fried rice with fried eggs or chicken. The conversation was fine, and familiar. Then we went to visit with a farmer…who was also a collector. Interesting turn of events. We went up to one of the farms that he collects from. A husband and wife came down to see us, sacks filled with cherry. Sabri- the collector-farmer, pulled out a handful of cherry to show us. It was as indiscriminate as the first bunch that we were shown. I got out one of my handy cherry selection cards and picked through the cherries in his hand, selecting just those that fit with the three thumbs up cherries. Sabri looked at them, picked up one cherry, and said that it was too ripe. My face must have registered some surprise. Sabri smiled, opened up the cherry, and showed me this:

Plain and simple, Sabri’s got game. He took us to a couple of farms that he tends. On one he showed us some old Abyssinia plants. On another, Bourbon. When we asked if he could keep those separate, he said maybe, but it would be very difficult. This wasn’t nudge-nudge wink-wink. This was an open and honest assessment that maybe he wouldn’t be able to do it. Even as the collector for and essentially manager of these farms, the idea of selective picking and lot separation posed challenges to the point where he was hesitant to guarantee that he could. We expressed great interest, saying that if he would try to do it, we wanted to try it and would be happy to buy it. We told him that by starting with a smaller lot or two we would be able to buy it either way, no guarantee required on his part. Jason stressed numerous times that we weren’t going to ask for any extra work without paying for it. Sabri said that he would try. This was in November. Fast forward to January. Two samples show up in our lab:

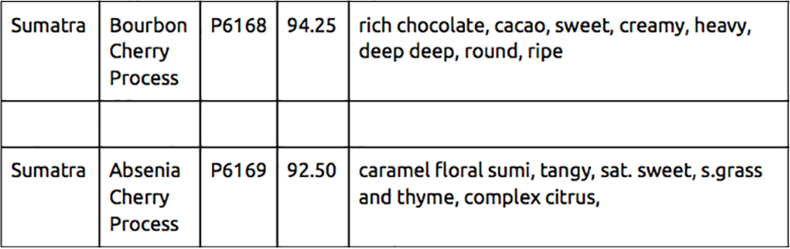

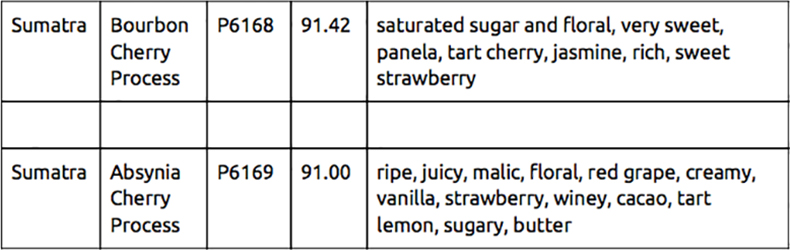

Pretty good 🙂 Now, pre-ships are not arrivals, and this certainly holds true for Sumatra. That said, these were blinded on a table with two other standard cup Sumatrans and the difference was glaring. Because, why not… Fast forward to May. Two lots show up in our warehouse:

Like I said, Sabri’s got game. One thing that I’d like to stress here is that these are Wet-Hulled Sumatran Coffees- and this is exactly what is so remarkable about them. They exemplify the character of the origin and the wet hulled process. You don’t mistake them for washed coffees just because they’re clean. You do reassess your take on wet hulled and Sumatran coffees.

Like I said, Sabri’s got game. One thing that I’d like to stress here is that these are Wet-Hulled Sumatran Coffees- and this is exactly what is so remarkable about them. They exemplify the character of the origin and the wet hulled process. You don’t mistake them for washed coffees just because they’re clean. You do reassess your take on wet hulled and Sumatran coffees.

Do we need to improve Sumatran coffees? Advance or help them progress? What does

that even mean? Does it mean destroying Sumatran coffees? While I am a person who

puts things in my mouth professionally and as such am happy to see fewer and fewer defects, I prefer to not throw the bath water out with the baby. The reason I am psychologically able to stay interested and engaged is exactly this dynamic (it’s nonlinear!) evolution. Did we go down and ask questions, poke around some, make a request and take a risk, ultimately to find something really amazing? Yes, we did that. Did we change Sumatran coffee for the better? No. Come on, man, Sumatran coffee just changed us for the better. Did we create something new? Nope. If anyone did, it was Sabri and the nonlinear coffee loops. They’d been doing it for a long time, accumulating and organizing for a long time. We may have catalyzed, but Sabri is the attractor in all this, and the nonlinear coffee loops we’re seeing emerge aren’t done by a long shot.

Very Best Wishes,

Ian