Transparency

A complicated term with an equally complicated history in the coffee industry. When it comes down to it, we’re talking about fairness; ensuring that everyone involved bringing coffee from seed to cup is correctly compensated for their work, the environment is treated with respect, and we all have contributed to improving livelihoods through the purchase of coffee. At Cafe Imports, this improving the livelihood of small-holder farmers through the purchase of coffee is a core tenant of our business. Quite simply, we believe that paying more than the prevailing specialty price for coffee helps protect the future of specialty coffee by carving a pathway for individual farmers to improve their quality of life. We are not and will never be a commodity company. We put our money where our mouth is. Calls for financial transparency in coffee are rooted in a simple question we’ve all asked ourselves:

“How can I make the most impact with my purchase?”

We often get asked by roasters to quantify this impact with another question…

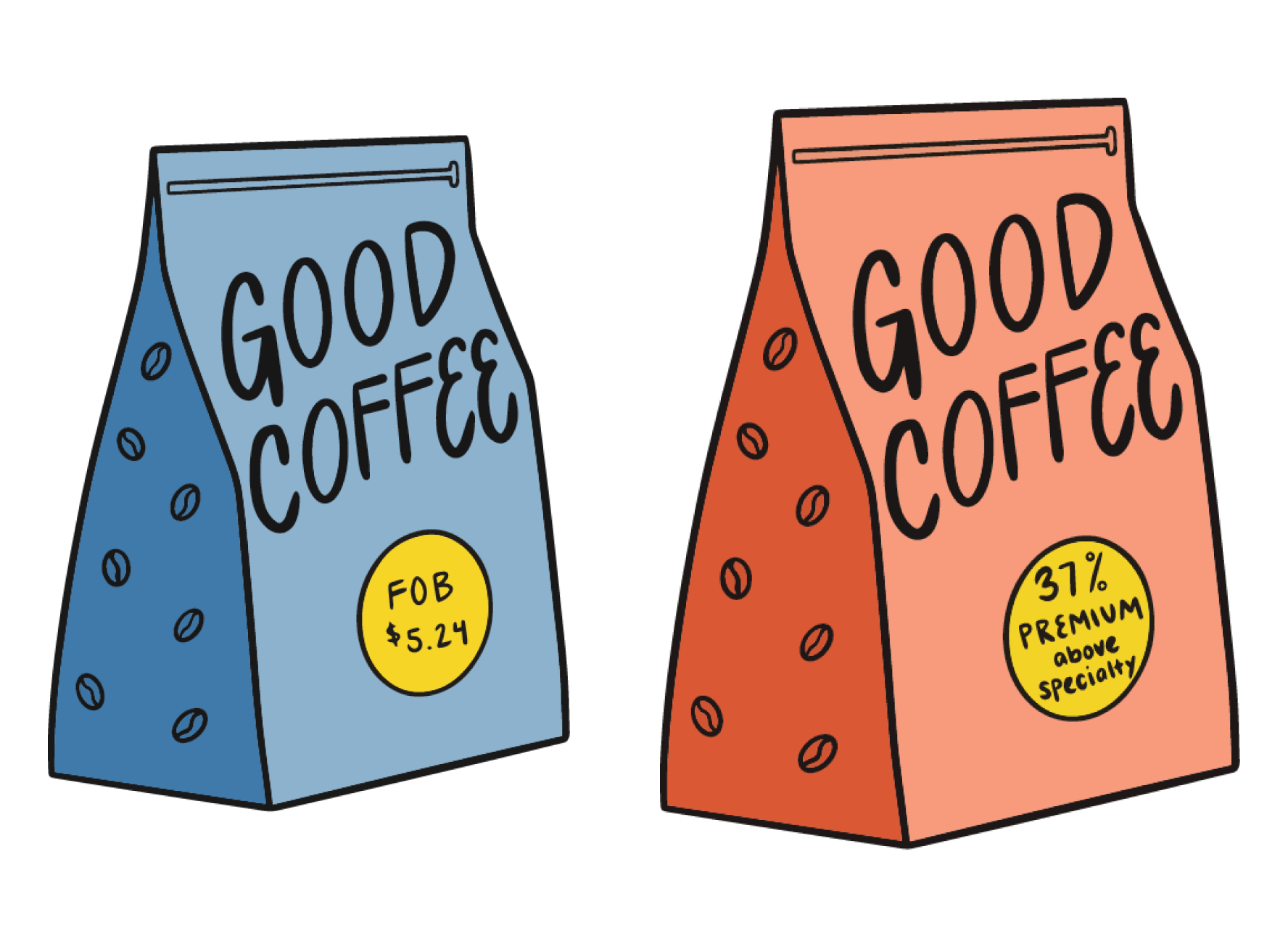

“What was the Farmgate or FOB price?”

While this information can be a piece of the puzzle when evaluating equity, there are some important considerations to take into account when asking this question. Consent, cultural context, accessibility of information, and economic factors at the time of purchase to name a few. We’re going to delve into some of the aspects of transparency, who is involved when, impacts of making information transparent, and some factors to consider in those decisions by looking at an example coffee value chain and how prices are calculated. We’ll look at how we approach these decisions and since they often include people that are historically disadvantaged and distanced from the end use of their information, from the beginning we need to ask ourselves some tough questions. Is everyone in the value chain in a position to say “no” to the sharing of information if they don’t want to or it endangers them (particularly important for location and financial data)? Does everyone agree ahead of time how the information will be used and by who? And most importantly, has everyone from seed to cup consented to the sharing of their information in the ways previously agreed upon? And finally, is the information I am presenting to end consumers helping to demonstrate the intended impact or further complicating the understanding with a broad scope of numbers without context?

Note: all numbers here are hypothetical and for sake of discussion unless noted otherwise. If you would like to be a part of our research and transparency efforts, drop us an email below!

What is transparency?

Transparency generally refers to the gathering, sharing, and disclosure of information about a supply chain to better understand the social and environmental impacts, and how value is distributed amongst the many hands it takes to get from point A to point B. In the coffee industry the conversation tends to focus on the financial transactions but can also include information about the origin of the coffee, the conditions under which it was grown, ethical, political, and social considerations such as labor or anti-corruption practices, and environmental concerns. Let’s remember that transparency directly overlaps with the three pillars of sustainability, they can apply to every actor in the supply chain and can be considered at any point in a coffee’s journey from seedling to customer.

Financial

The transactions that took place to grow, process, export, import, roast, and finally sell the coffee to the consumer. This is any financial data that contributed to the overall value lost or derived by each actor. Some examples include the exchange rate, cost of labor or farm inputs, quality premiums, cooperative fees, or certification differentials. To make financial data transparency, accurate and open recording of this data is required by everyone each time coffee exchanges hands.

Social

The practices of each actor regarding human rights, fair labor practices, health, safety, and education. Both an ethical and legal consideration, we view responsible social practices as key to building open and trustworthy relationships. These practices look very different depending on which step in the value-chain we are speaking about and local laws and standards.

Environmental

The management practices of an operations positive and negative impacts on the environment. As part of an industry that relies fully upon healthy ecosystems, it is critical that we monitor these impacts, working together to reduce our environmental footprint. For farmers and producers this might look like protecting native forests, eliminating the use of chemicals and ensuring water is cleaned after use in milling. On the consumption end of the supply chain the first thing to focus on is usually reducing or eliminating waste, especially plastics from packaging, shifting to renewable energy sources, and minimizing emissions from transportation.

To understand how these three pillars contribute to the overall picture, we’re going to need to know some basics about a typical supply-chain and some terminology. If you’re a seasoned coffee pro, you can skip this section and head down the section Quantifying Our Efforts for more about our price premium model.

A basic supply chain and common terms.

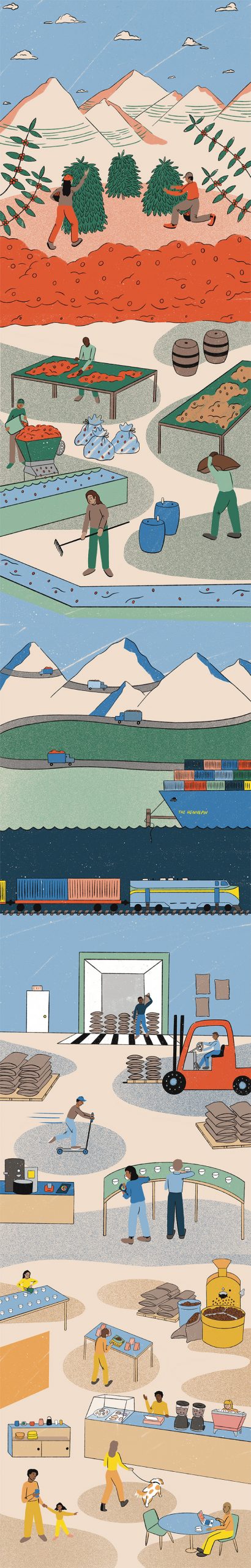

We need a rough understanding of a basic coffee supply chain to talk about how it is bought, sold, and ultimately factors that influence transparency. Here’s a very quick refresher to get us started. Remember that there’s a lot of different people and business models to perform these services, so sometimes it will be a farmer doing all their own dry/wet milling and exporting, or it could be an exporter that outsources the milling, or perhaps it’s a farmer owned cooperative that does the processing for a fee, the methods are as unique and diverse as coffee itself.

Planting/Cultivation/Harvesting

Planting coffee isn’t quite as simple as sticking the seed in the ground and waiting. Usually, coffee trees start life in a protected greenhouse as they sprout and are moved into the field once they are strong enough. Most species take 3-4 years to mature and begin producing fruit. This fruit, what we commonly call a coffee “cherry”, can be handpicked if focusing on quality, or machine harvested for larger production. This can happen once a year in most coffee-growing regions, but in countries that lie along the equator or in warmer climates, there may be two harvests annually. If the farmer sells the coffee in cherry at this point or continues to process themselves before sale, that price is called the “Farmgate” price and should cover the cost of production, be sufficient to cover personal expenses, and include a profit margin.

Farmgate price often is a raw price for unprocessed and unmilled cherry or parchment, so this price is relevant in the context of where it was sold and how it was processed, but tough to compare country to country. For example, payment in Pesos (Avg 4,323.28COP to $1.00 or €0.92 in 2023) per carga (125kg) in Colombia as a farmgate price is not directly comparable to Costa Rican Colones (Avg 544CRC to $1.00 or €0.97 in 2023 per quintale (46kg or 101lbs) of cherry in Costa Rica. Those prices look very different depending on if the coffee as delivered in cherry or in parchment, the Green Been Equivalent or yield factor for that farm, and exchange rate at time of sale which means that they don’t demonstrate equity to an end consumer without additional context.

Processing/Milling

After harvesting, the cherries are processed, usually with one of two broad methods and there are new variations and experimental methods being introduced all the time: the dry method, where cherries are spread out in the sun to dry before the skin and mucilage are removed, and the wet method, which involves removing the pulp immediate, fermenting, and then drying the bean with only the parchment skin on. For either method, once the beans are dry, they are hulled or “dry-milled”, where the outer layers of the dried cherry and/or parchment are removed. This step also often includes polishing to remove any remaining dried skin, grading and sorting the beans based on size and weight. Often, this is the first time the coffee will be tasted and the quality and attributes will be noted. It’s common for samples to be sent at this point to exporters, imports, or potential customers for further assessment, we call these Pre-Shipment Samples (PSS).

Note that there are two points here where the coffee is losing weight. Once when the seed is removed from the fruit, cleaned, and dried. Then again when they are graded. This means that to end up with say 1kg of coffee ready to export, we need more cherries by weight to start with. This is often calculated by something called a “Green Been Equivalent” (GBE). A simple ratio to calculate how much weight in cherry it takes to have an output of a specific weight of finished coffee. GBE can be different depending the on the processing standards , allowed screensize, even ripeness of the fruit when harvested. which again varies greatly by origin or from farm to farm. In Brazil, you may allow down to 15 screen size which would mean this % would be higher, but in Kenya for AA, this may be lower. This adds a wrinkle into the relevancy of Farmgate price without a strong geographic understanding of coffee agronomy in the country being discussed.

Exporting

The processed and milled beans, now referred to as green coffee, are packed in sacks and moved to the port of departure and ultimately to the country of consumption. Importers usually work with Exporters to make this journey happen. The price paid by the Importer when the coffee arrives at port is called the “Free On Board” (FOB) and (if the exporter is a sustainable business) covers the costs of Farmgate/Processing/Milling/Domestic Transport and anything else arising from getting the coffee from farm to port and on the boat. In landlocked countries that need to export by truck or plane to the nearest port, it’s common to see prices reported as “Free on Truck” (FOT) or “Free Carrier” (FCA), which is the price when the coffee is loaded onto the truck in the case of FOT, or any vehicle in the case of FCA, to make the journey to port. Both of these prices include the exporter’s margin, which can vary dramatically depending on the business model of the exporter.

FOB is the most common request we get for financial transparency, but as you can see, this number may not always indicate the impact on the farmer without a strong understanding of the full geographic and economic picture of the purchase. Simply one exporter having a higher margin than another can make this number slightly misleading when trying to determine how much was paid to the farmer or producer.

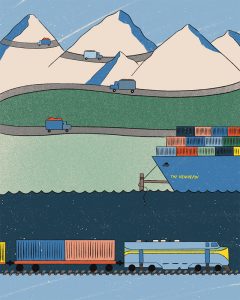

Importing

Once the “Free On Board” (FOB), “Free on Truck” (FOT), or “Free Carrier” (FCA) price has been paid and all the stacks of paperwork have been signed, the coffee is physically moved onto the ship, truck, or other transportation method (sometime plane or train) for shipping to the point of import. While every effort is made to minimize the time this takes, moving the coffee can take anywhere from a few days to months depending on the shipping method, route the coffee must take, and the perils encountered along the way.

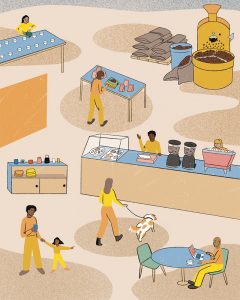

Sensory Analysis/Warehousing/Final Shipping

Upon arrival at its destination, green coffee samples are roasted, tasted, and graded by sensory scientists to assess that their quality and flavor profile are consistent with the pre-ship sample. The green coffee is stored in a climate-controlled environment until it is sold and shipped to the Roaster. These handling and warehousing costs are often called “Ex-Works” or “Ex-Warehouse” and cover the cost of doing business by the Importer.

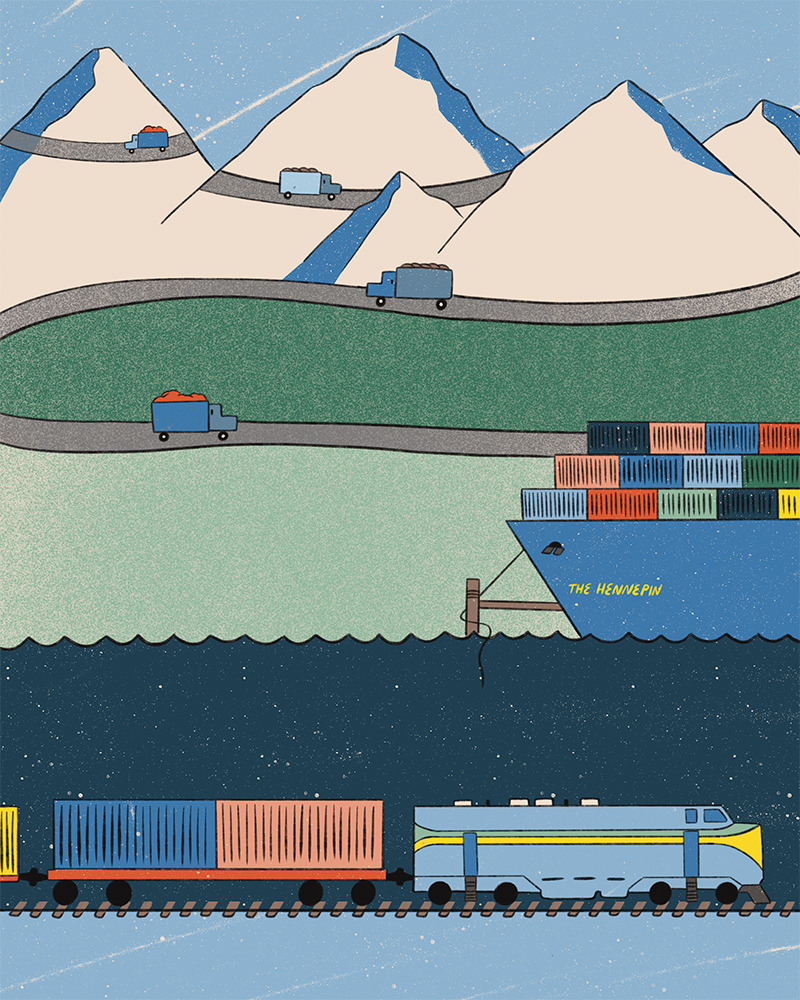

Roasting/Packaging/Retailing

Roasters purchase the green coffee and prep it for serving or distribution to their customers. Roasting, packaging, distribution, and retailing are the final stop in the coffees journey to becoming a final product ready for consumption

Consumption

Customers enjoy the results! The “Retail Price” of the final cup or bag covers the remaining costs incurred and profit by the Roaster.

Planting/Cultivation/Harvesting

Planting coffee isn’t quite as simple as sticking the seed in the ground and waiting. Usually, coffee trees start life in a protected greenhouse as they sprout and are moved into the field once they are strong enough. Most species take 3-4 years to mature and begin producing fruit. This fruit, what we commonly call a coffee “cherry”, can be handpicked if focusing on quality, or machine harvested for larger production. This can happen once a year in most coffee-growing regions, but in countries that lie along the equator or in warmer climates, there may be two harvests annually. If the farmer sells the coffee in cherry at this point or continues to process themselves before sale, that price is called the Farmgate price and should cover the cost of production, be sufficient to cover personal expenses, and include a profit margin.

Planting coffee isn’t quite as simple as sticking the seed in the ground and waiting. Usually, coffee trees start life in a protected greenhouse as they sprout and are moved into the field once they are strong enough. Most species take 3-4 years to mature and begin producing fruit. This fruit, what we commonly call a coffee “cherry”, can be handpicked if focusing on quality, or machine harvested for larger production. This can happen once a year in most coffee-growing regions, but in countries that lie along the equator or in warmer climates, there may be two harvests annually. If the farmer sells the coffee in cherry at this point or continues to process themselves before sale, that price is called the Farmgate price and should cover the cost of production, be sufficient to cover personal expenses, and include a profit margin.

Farmgate price often is a raw price for unprocessed and unmilled cherry or parchment, so this price is relevant in the context of where it was sold and how it was processed, but tough to compare country to country. For example, payment in Pesos (Avg 4,323.28COP to $1.00 or €0.92 in 2023) per carga (125kg) in Colombia as a farmgate price is not directly comparable to Costa Rican Colones (Avg 544CRC to $1.00 or €0.97 in 2023 per quintale (46kg or 101lbs) of cherry in Costa Rica. Those prices look very different depending on if the coffee as delivered in cherry or in parchment, the Green Been Equivalent or yield factor for that farm, and exchange rate at time of sale which means that they don’t demonstrate equity to an end consumer without additional context.

Processing/Milling

After harvesting, the cherries are processed, usually with one of two broad methods and there are new variations and experimental methods being introduced all the time: the dry method, where cherries are spread out in the sun to dry before the skin and mucilage are removed, and the wet method, which involves removing the pulp immediate, fermenting, and then drying the bean with only the parchment skin on. For either method, once the beans are dry, they are hulled or “dry-milled”, where the outer layers of the dried cherry and/or parchment are removed. This step also often includes polishing to remove any remaining dried skin, grading and sorting the beans based on size and weight. Often, this is the first time the coffee will be tasted and the quality and attributes will be noted. It’s common for samples to be sent at this point to exporters, imports, or potential customers for further assessment, we call these Pre-Shipment Samples (PSS).

After harvesting, the cherries are processed, usually with one of two broad methods and there are new variations and experimental methods being introduced all the time: the dry method, where cherries are spread out in the sun to dry before the skin and mucilage are removed, and the wet method, which involves removing the pulp immediate, fermenting, and then drying the bean with only the parchment skin on. For either method, once the beans are dry, they are hulled or “dry-milled”, where the outer layers of the dried cherry and/or parchment are removed. This step also often includes polishing to remove any remaining dried skin, grading and sorting the beans based on size and weight. Often, this is the first time the coffee will be tasted and the quality and attributes will be noted. It’s common for samples to be sent at this point to exporters, imports, or potential customers for further assessment, we call these Pre-Shipment Samples (PSS).

Note that there are two points here where the coffee is losing weight. Once when the seed is removed from the fruit, cleaned, and dried. Then again when they are graded. This means that to end up with say 1kg of coffee ready to export, we need more cherries by weight to start with. This is often calculated by something called a Green Been Equivalent (GBE). A simple ratio to calculate how much weight in cherry it takes to have an output of a specific weight of finished coffee. GBE can be different depending the on the processing standards , allowed screensize, even ripeness of the fruit when harvested. which again varies greatly by origin or from farm to farm. In Brazil, you may allow down to 15 screen size which would mean this % would be higher, but in Kenya for AA, this may be lower. This adds a wrinkle into the relevancy of Farmgate price without a strong geographic understanding of coffee agronomy in the country being discussed.

Exporting

The processed and milled beans, now referred to as green coffee, are packed in sacks and moved to the port of departure and ultimately to the country of consumption. Importers usually work with Exporters to make this journey happen. The price paid by the Importer when the coffee arrives at port is called the Free On Board (FOB) and (if the exporter is a sustainable business) covers the costs of Farmgate/Processing/Milling/Domestic Transport and anything else arising from getting the coffee from farm to port and on the boat. In landlocked countries that need to export by truck or plane to the nearest port, it’s common to see prices reported as Free on Truck (FOT) or Free Carrier (FCA), which is the price when the coffee is loaded onto the truck in the case of FOT, or any vehicle in the case of FCA, to make the journey to port. Both of these prices include the exporter’s margin, which can vary dramatically depending on the business model of the exporter.

The processed and milled beans, now referred to as green coffee, are packed in sacks and moved to the port of departure and ultimately to the country of consumption. Importers usually work with Exporters to make this journey happen. The price paid by the Importer when the coffee arrives at port is called the Free On Board (FOB) and (if the exporter is a sustainable business) covers the costs of Farmgate/Processing/Milling/Domestic Transport and anything else arising from getting the coffee from farm to port and on the boat. In landlocked countries that need to export by truck or plane to the nearest port, it’s common to see prices reported as Free on Truck (FOT) or Free Carrier (FCA), which is the price when the coffee is loaded onto the truck in the case of FOT, or any vehicle in the case of FCA, to make the journey to port. Both of these prices include the exporter’s margin, which can vary dramatically depending on the business model of the exporter.

FOB is the most common request we get for financial transparency, but as you can see, this number may not always indicate the impact on the farmer without a strong understanding of the full geographic and economic picture of the purchase. Simply one exporter having a higher margin than another can make this number slightly misleading when trying to determine how much was paid to the farmer or producer.

Importing

Once the Free On Board (FOB), Free on Truck (FOT), or Free Carrier (FCA) price has been paid and all the stacks of paperwork have been signed, the coffee is physically moved onto the ship, truck, or other transportation method (sometime plane or train) for shipping to the point of import. While every effort is made to minimize the time this takes, moving the coffee can take anywhere from a few days to months depending on the shipping method, route the coffee must take, and the perils encountered along the way.

Once the Free On Board (FOB), Free on Truck (FOT), or Free Carrier (FCA) price has been paid and all the stacks of paperwork have been signed, the coffee is physically moved onto the ship, truck, or other transportation method (sometime plane or train) for shipping to the point of import. While every effort is made to minimize the time this takes, moving the coffee can take anywhere from a few days to months depending on the shipping method, route the coffee must take, and the perils encountered along the way.

Sensory Analysis/Warehousing/Final Shipping

Upon arrival at its destination, green coffee samples are roasted, tasted, and graded by sensory scientists to assess that their quality and flavor profile are consistent with the pre-ship sample. The green coffee is stored in a climate-controlled environment until it is sold and shipped to the Roaster. These handling and warehousing costs are often called “Ex-Works” or “Ex-Warehouse” and cover the cost of doing business by the Importer.

Roasting/Packaging/Retailing

Roasters purchase the green coffee and prep it for serving or distribution to their customers. Roasting, packaging, distribution, and retailing are the final stop in the coffees journey to becoming a final product ready for consumption

Roasters purchase the green coffee and prep it for serving or distribution to their customers. Roasting, packaging, distribution, and retailing are the final stop in the coffees journey to becoming a final product ready for consumption

Consumption

Customers enjoy the results! The Retail Price of the final cup or bag covers the remaining costs incurred and profit by the Roaster.

So what are Farmgate and FOB/FOT/FCA prices?

Farmgate is a catch all term for the price paid directly to the farmer or producer for the coffee, while FOB/FOT/FCA is the price paid by the importer to the exporter at the point the coffee is loaded onto the ship (FOB/FCA), truck (FOT/FCA) or plane (FCA).

Farmgate

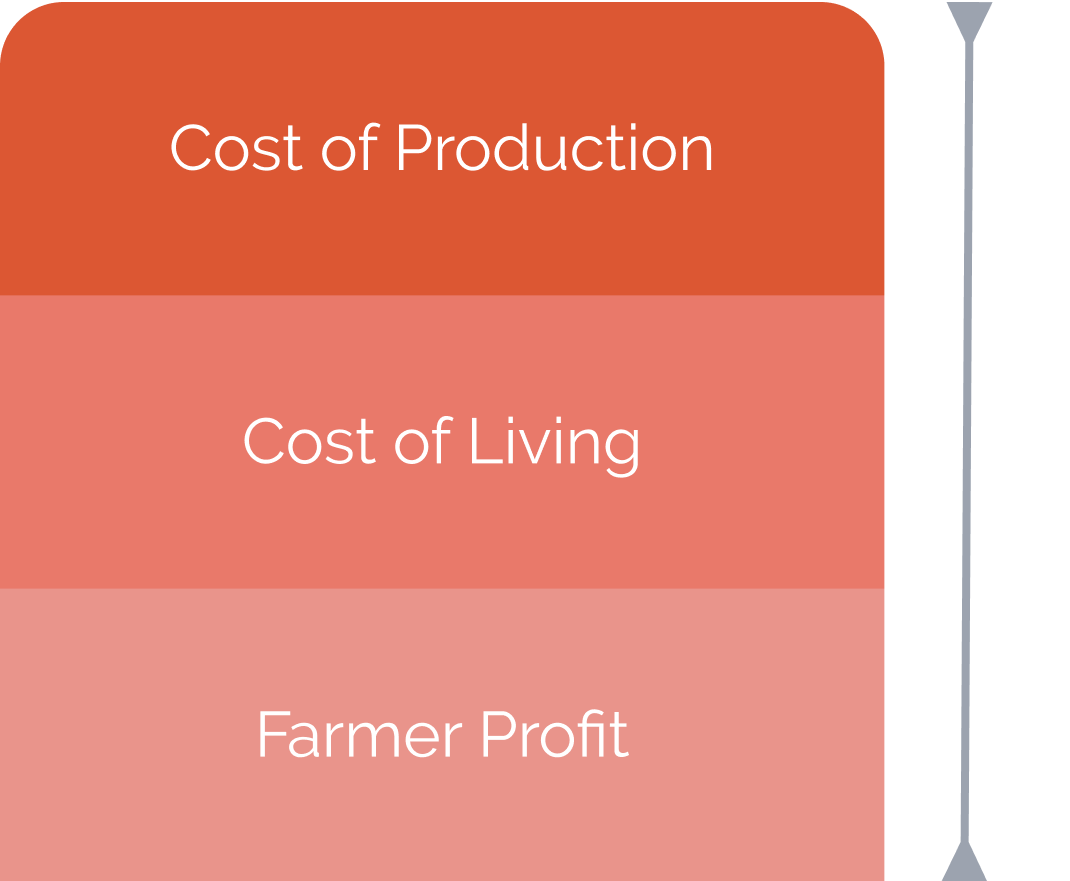

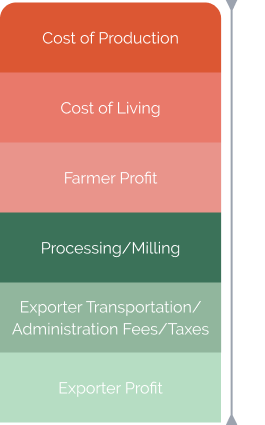

The price paid to the producer, usually near the farm, often for unprocessed or partially process coffee either in Cherry or Parchment, but at times exportable green when they process the coffee themselves. This price can fluctuate throughout the harvest due to changes in quality, movement of the C-Market, or increases and decreases in supply and demand for similar coffees. For a farm to be sustainable, this needs to cover the cost of living, cost of production, and include profits.

Free On Board/Truck/Carrier (FOB/FOT/FCA)

The price paid by the Importer to the Exporter is called the Free On Board (FOB), Free on Truck (FOT), or Free Carrier (FCA) and if the exporter is a sustainable business covers the costs of Farmgate/Processing/Milling/Domestic Transport and anything else arising from getting the coffee from farm to port and on board the ship or truck.

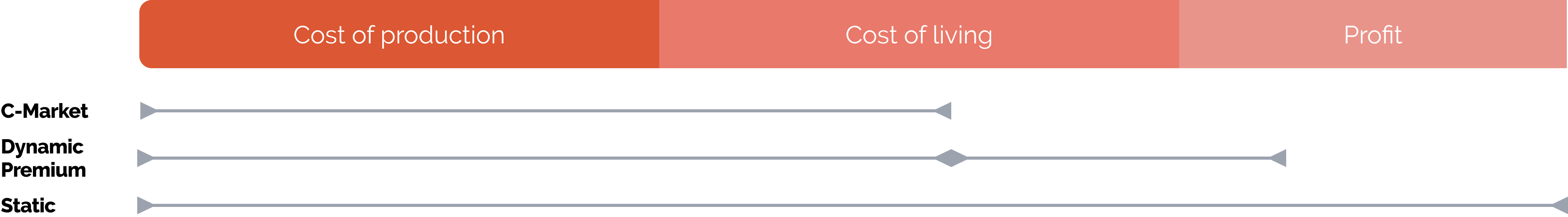

What are these prices based on?

The price of specialty coffee is largely benchmarked against the Commodity Market (C-Market) which serves as a constantly fluctuating guide and price floor for Arabica coffee. Specialty coffee (commonly referred to as differentiated coffee) will then be purchased for a premium above the current C-Market price. This premium can be tied to a number of other factors including certifications, quality, social impact, unique characteristics, or sometimes just a great story that we connect with! Whether the price is pre-agreed upon, known as Static pricing, or is an amount above C-Market and continues to move with it until a specific time, known as Dynamic pricing, both sellers and buyers use the C-Market as a reference point.

Commodity or C-Market

The C-Market, or the “C” price, is a global benchmark for the trading of Arabica coffee. It operates similarly to a stock exchange for commodities, where green Arabica coffee is traded in the form of futures contracts on the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE) in New York City. These futures contracts are agreements to buy or sell a commodity (in this case Coffee) at a predetermined price at a specified future date.

The price of coffee on the C-Market fluctuates based on supply and demand, as well as on speculation about future supply and demand. This means the price per pound of coffee can change significantly from one day to the next. For instance, the C price can vary dramatically, which can impact everyone from producers to roasters to consumers. Factors such as weather conditions, disease outbreaks affecting harvests, and global economic factors can all influence these price changes.

Dynamic

Dynamically priced coffees respond to market fluctuations. This method of setting the price of coffee accounts for various factors, such as quality, origin, market conditions, and futures market prices. This means that the price for a coffee can fluctuate from day to day, even during the middle of the harvest season. Dynamic pricing allows for flexibility to react to market conditions, ensuring that both buyers and sellers can reach a fair agreement that reflects the current value of the coffee being traded. This of course comes with risks in instances of an overall C-Market downturn.

Static

Static pricing is simple, you agree on a set price that does not change in response to market forces and that is what is paid. This type of pricing can be an advantage for buyers or sellers who wish to lock in costs and revenues without the risk of price volatility affecting their margins or profitability. Static pricing is often used in direct trade agreements or specialty coffee trading where the quality, relationship, or specific attributes of the coffee are valued beyond the commodity market price.

This price is agreed upon within the context of the C-Market at the time directly or indirectly. If a fair price is established collaboratively then the C-Market increases, that fair price may not seem so fair any more given the alternative of a higher C-Market.

Don’t forget geographic and economic context.

Most consumers in non-coffee producing countries, encounter the price of coffee either in drink form or roasted bag form, far removed from the farm and the pricing of the raw material meticulously chosen by the roaster. So does Farmgate or FOB/FOT alone tell the whole story of value distribution? Let’s look at three very simplified scenarios.

Bringing it all together: An example from Honduras.

Since each actor can be involved in any or all aspects of transparency, let’s use an example built on our list of financial transparency items from above to get familiar with the terms and some ways they can be applied. There is no way to embody the complexity and uniqueness of every coffee relationship so to keep it simple, we’ll set the scene.

We’re going to say that we’re talking about the journey of a microlot specialty coffee grown by a smallholder in Honduras, which was wet milled by the farmer, dry milled and graded by a cooperative near the farm, exported, imported, then roasted and consumed in the central United States by a roaster with both a wholesale and retail operation. Finally, we’re also going to use the 2023 average commodity market (C-market) of $1.72, and say that this coffee was purchased and sold for a fixed price across the entire supply chain.

The numbers below are for demonstration, they can vary drastically for a given coffee. Some examples of these variations would be the market factors above, cost of farm inputs, cost of labor, lot size, shipping method and routes, location of the roastery in relation to the point of import or storage, and whether or not the final sale is via wholesale or traditional retail. Middle column is shown as percentage of final retail price per pound.

Planting, Cultivation, and Harvesting

Term: Farmgate

Includes everything it takes to grow and nurture coffee from a seedling to producing tree. Fertilization, pest management, weed control, rejuvenation, harvesting, sometimes post-harvest wet or dry-milling, replanting, and basic administrative costs. Farmgate should also cover a living income which is typically defined as providing a nutritious diet, housing, provision for unexpected events, and essential expenses such as education, healthcare, clothing and transportation.

Transparency Considerations

Financial

- C-Market a time of sale

- Exchange rate at time of sale

- Cost of farm inputs

- Cost of labor

- Land productivity

- Cost of transportation

- Quality

- Lot size

- Cooperative fees

- Processing performed

- Certification differentials

- Premium differentials for extrinsic factors

Social

- Respect for indigenous and local communities

- Involuntary labor

- Child and young workers

- Discrimination

- Fair and living wage standards

- Health and safety provisions

Environmental

- Forest protection

- Soil conservation

- Water conservation and purity

- Biodiversity protections

- Farm location, boundaries, and environmental conditions

- Use of chemicals (fungicide, herbicide, pesticide, etc)

Processing, Milling, and Export

Terms: Free On-Board/Free-On-Truck/Free Carrier

Costs covered: The Farmgate price paid to the farmer in whatever form the coffee was delivered (in cherry, parchment, sorted or unsorted), additional processing, sorting for defects, size screening, packaging (bagging in grainpro, jute bags, and printing bag marks), domestic transportation from between point of purchase to warehouse, mill and port, customs clearance paperwork and taxes.

Transparency Considerations

Financial

- C-Market

- Domestic transportation

- Cost of labor

- Cost of coffee in cherry

- Loss during milling

- Certification differentials

- Lot size

Social

- Respect for indigenous and local communities

- Involuntary labor

- Child and young workers

- Discrimination

- Fair and living wage standards

- Health and safety provisions

Environmental

- Emissions

- Water conservation and purity

- Biodiversity protections

- Waste management and reduction

- Use of chemicals

Import

Terms: Ex-Works/Ex-Warehouse

Costs covered: The Free-On-Board price paid to the exporter, shipping from port of departure, arrival port handling, customs and import taxes, insurance, shipping from port to warehouse, warehousing, quality control, packaging, labor, marketing and financing/interest.

Transparency Considerations

Financial

- Labor

- Cost of international freight

- Cost of domestic freight

- Warehousing costs

- Quality loss

- Lot size

Social

- Diversity and equity practives

- Fair wage and labor standards

- Health and safety training

- Ethical marketing practices

Environmental

- Energy use

- Emissions

- Waste management and reduction

Roasting, Packing, Distribution, and Retailing

Term: Retail

Costs covered: Price paid to importer, shipping from warehouse to roaster, facilities, equipment, labor, packaging, retailing, financing/interest and marketing.

Transparency Considerations

Finanacial

- Labor

- Occupancy expenses

- Delivery expenses

- COGS

Social

- Diversity and equity practices

- Fair wage and labor standards

- Healtha and safety training

- Ethical marketing practices

Environment

- Energy use

- Emissions

- Waste management and reduction

Cost of Production

6%

Cost of Living and Profit

5.0%

Processing/Milling

3.4%

Transportation/Export Fees/Taxes

6.2%

Exporter Profit

1.4%

Shipping/Transportation

1.3%

Import Fees/Taxes/Warehousing/Labor

6.2%

Importer Profit

1.0%

Roaster Expenses

45.0%

Weight Loss

14%

Roaster Profit

10.5%

Planting, Cultivation, and Harvesting

Term: Farmgate

Includes everything it takes to grow and nurture coffee from a seedling to producing tree. Fertilization, pest management, weed control, rejuvenation, harvesting, sometimes post-harvest wet or dry-milling, replanting, and basic administrative costs. Farmgate should also cover a living income which is typically defined as providing a nutritious diet, housing, provision for unexpected events, and essential expenses such as education, healthcare, clothing and transportation.

Transparency Considerations

Financial

- C-Market a time of sale

- Exchange rate at time of sale

- Cost of farm inputs

- Cost of labor

- Land productivity

- Cost of transportation

- Quality

- Lot size

- Cooperative fees

- Processing performed

- Certification differentials

- Premium differentials for extrinsic factors

Social

- Respect for indigenous and local communities

- Involuntary labor

- Child and young workers

- Discrimination

- Fair and living wage standards

- Health and safety provisions

Environmental

- Forest protection

- Soil conservation

- Water conservation and purity

- Biodiversity protections

- Farm location, boundaries, and environmental conditions

- Use of chemicals (fungicide, herbicide, pesticide, etc)

Processing, Milling, and Export

Terms: Free On-Board/Free-On-Truck/Free Carrier

Costs covered: The Farmgate price paid to the farmer in whatever form the coffee was delivered (in cherry, parchment, sorted or unsorted), additional processing, sorting for defects, size screening, packaging (bagging in grainpro, jute bags, and printing bag marks), domestic transportation from between point of purchase to warehouse, mill and port, customs clearance paperwork and taxes.

Transparency Considerations

Financial

- C-Market

- Domestic transportation

- Cost of labor

- Cost of coffee in cherry

- Loss during milling

- Certification differentials

- Lot size

Social

- Respect for indigenous and local communities

- Involuntary labor

- Child and young workers

- Discrimination

- Fair and living wage standards

- Health and safety provisions

Environmental

- Emissions

- Water conservation and purity

- Biodiversity protections

- Waste management and reduction

- Use of chemicals

Import

Terms: Ex-Works/Ex-Warehouse

Costs covered: The Free-On-Board price paid to the exporter, shipping from port of departure, arrival port handling, customs and import taxes, insurance, shipping from port to warehouse, warehousing, quality control, packaging, labor, marketing and financing/interest.

Transparency Considerations

Financial

- Labor

- Cost of international freight

- Cost of domestic freight

- Warehousing costs

- Quality loss

- Lot size

Social

- Diversity and equity practives

- Fair wage and labor standards

- Health and safety training

- Ethical marketing practices

Environmental

- Energy use

- Emissions

- Waste management and reduction

Roasting, Packing, Distribution, and Retailing

Term: Retail

Costs covered: Price paid to importer, shipping from warehouse to roaster, facilities, equipment, labor, packaging, retailing, financing/interest and marketing.

Transparency Considerations

Financial

- Labor

- Occupancy expenses

- Delivery expenses

- COGS

Social

- Diversity and equity practices

- Fair wage and labor standards

- Healtha and safety training

- Ethical marketing practices

Environment

- Energy use

- Emissions

- Waste management and reduction

This example uses averaged data from Cafe Imports as well as – Cadena, Alejandro. “A Study on Costs of Production in Latin America,” 2019, Carpio, Carlos E., Luis A. Sandoval, and Mario Muñoz. “Cost and Profitability Analysis of Producing Specialty Coffee in El Salvador and Honduras.” HortTechnology 33, no. 1 (February 2023): 8–15. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTTECH05028-22, “2017 Roaster/Retailer Financial Benchmarking Report,” n.d. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/584f6bbef5e23149e5522201/t/6012eacaf8928e729006cb0e/1611852517832/SCA_BenchmarkingReport_PRINT.pdf., “Fairtrade Living Income Report 2023,” n.d. https://www.fairtrade.net/library/fairtrade-living-income-progress-report-2023.

Quantifying our efforts.

If we’re trying to make the most positive impact with our purchase decisions, it’s tempting to try to quantify it with a single number (Farmgate, FOB/FOT/FCA, Ex-works or Retail Price). But how do we know which number(s) to use? Variations in weather, quality, lot size, exchange rates, cost of labor, cost of farm inputs, farm yield, and many other factors all influence the overall profitability and viability of each actor in the value chain, making these numbers mostly irrelevant on their own. Many farmers face historic lack of access to the resources and markets necessary to build a sustainable livelihood from coffee farming so it’s important to look at the overall sustainability context and include the social and environmental impacts in this decision making as well, doing what we can, where we can.

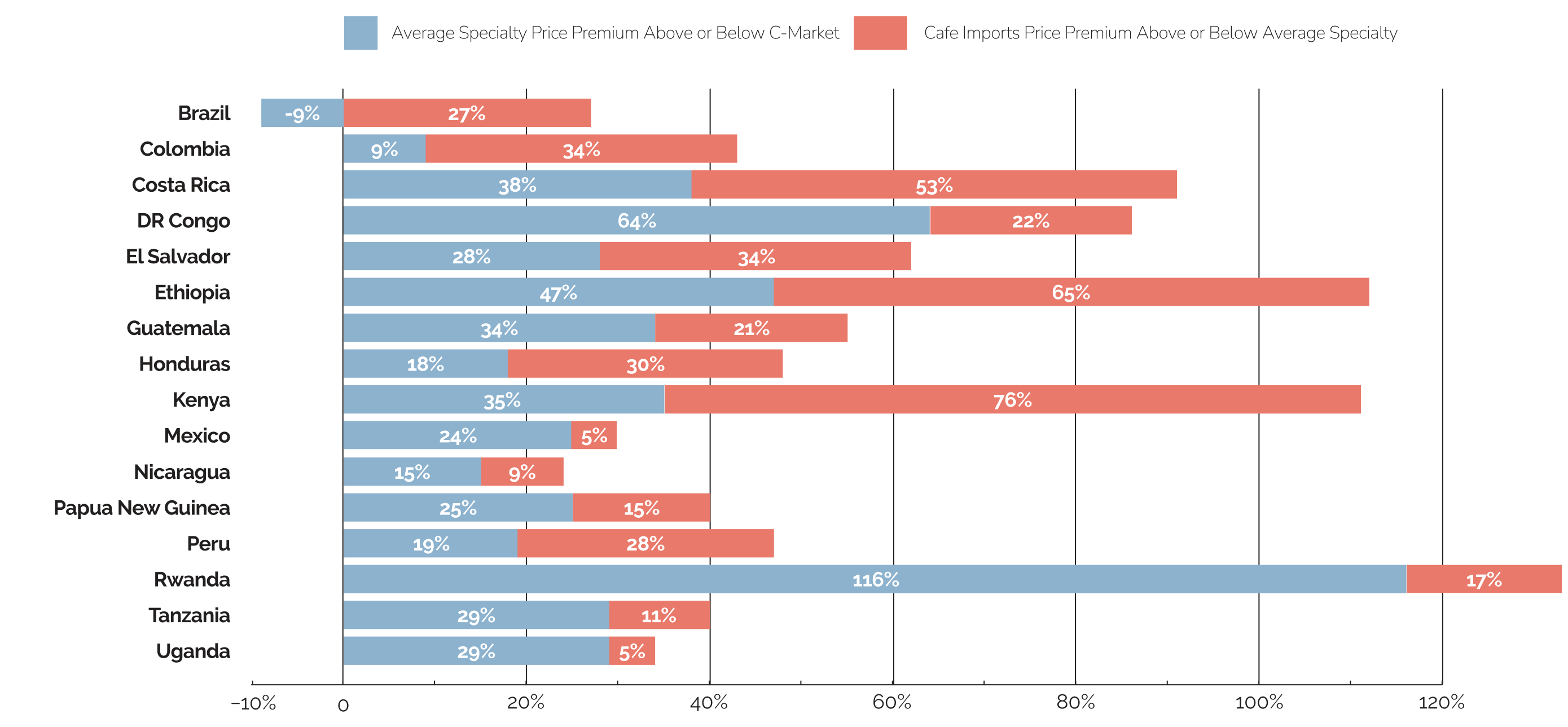

What we have done is taken a broad approach to our price premiums by putting them into context both as premiums above the C market and premiums paid above the going specialty rate by country. While this is still very imperfect, utilizing the going “specialty rate” for each country by deep research into each geographic area in which we work provided us more context with what the open market determined is a “fair” value for specialty coffee. Our premiums paid in this context we believe are much more compelling to a consumer to understand impact as a percentage over alternative sales. The next iteration of this model will look more like understanding cost of production by origin or region and placing our premiums paid in context to a living income in specific geographic areas. This approach also allows us to group information together in a way that protects farmer’s sensitive financial information and allows us to not have to ask a question of consent from our position of privilege.

Relationship building, trust, and Supplier Agreements.

To paint a complete picture we need not just the financial snapshot at the time the coffee is purchased, but a deeper understanding of the social and environmental needs of the community. Most of the counterparties we work with we’ve known for decades. We certainly have not visited every individual small-holder farmer we have ever bought coffee from, but we do have close relationships with many and certainly have visited with all exporting companies we work with. A lot of time and energy is spent seeing how companies operate, learning how they treat and respect the environment, talking about the culture they have developed in their company, farm, or mill, and asking some simple questions of them outlined in our Supplier Impact Standards. Sometimes this is a gut feeling or observation. Most often, pricing is determined collaboratively alongside the farmers growing the coffee. We have countless examples of town-hall meetings in a rural area where we ask the question “How can we meet your communities’ needs together?” and the resulting buying program is set up to address that. Similarly, you need to have some level of trust with the team bringing in your coffee. Ask questions of them and understand the impact they intend to have and how they are going about achieving that.

Consent

Ultimately the price at which coffee growers sell their coffee and the information about them and their farming practices, is their personal information to share or not share. We always want to be sensitive to the fact that as the buyers of their products in a relative position of power, even asking the question if they are ok with us publishing their sale price to us on the internet, is a weighted question. What if they don’t want their neighbors or other customers to know their sale price to us? What if they have personal reasons they do not want their financial information, farm practices or location published for the world to see? These are important questions to consider when trying to address the core question of “How can I ensure my purchase is having the most impact?” We believe there are ways to accomplish this without sharing sensitive financial information.

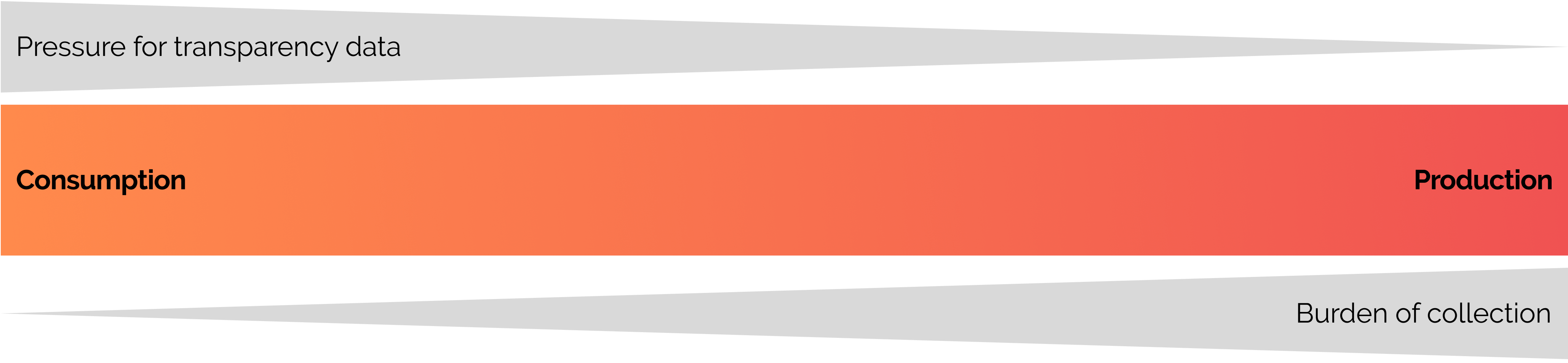

What you can do to get involved.

Transparency needs to be a roundabout…it should not be a one-way street. The distance between the places of coffee production, and places of consumption often means that collecting and sharing information becomes a purely extractive exercise, returning little value in exchange for the expense and effort it takes to make a supply chain transparent. If we’re asking how we can begin to understand value distribution, impacts on the environment, and if everyone in the value chain is treated fairly, all the actors must commit to the investment and respect required to make this happen.

Do I share what I pay myself, my employees, and my overall profitability as a business? What message does this send to my staff if they don’t know what I make or what their coworkers make? And whose decision is it to share that information – the employees or the owners? If I am asking a producer to allow me to open their books to the world because of my position of privilege, am I willing to do the same?

Roasters communicating cup characteristics and their customers preferences, importers ensuring they are fairly representing the coffee and the people behind it, exporters working with producers on quality assessment techniques or farm management, producers communicating the fluctuating costs of production and living; these are just a few examples of where transparency could be put to work to improve coffee for all.

For this to work we must all ask ourselves: are we all willing to participate in redistributing the burden and costs of transparency, and more importantly, share in the accountability?

Whether you’re a farmer, producer, exporter, roaster, or consumer, we need your feedback and input as we work towards deeper understanding of how value is distributed in the coffee value-chain. Contributing your experiences, anonymized data, research, or sending us your thoughts on any of what you read here is a first step towards making this complicated topic more accessible for all. We believe that transparency is a privilege and takes a lot of work by everyone. It’s earned through long-term relationships centered on trust, privacy, and a belief in mutual well-being. In short, we don’t want to view transparency as a commodity, but as an opportunity to build relationships that lead to deeper understanding of the people and places that make coffee great.