CAFE IMPORTS + BURUNDI

We have been visiting this tiny country (barely the size of Maryland) since 2006, cupping coffees from more than 50 different washing stations, trying to figure out what makes Burundi coffee so special, and so different—even from relatively nearby Rwanda, the country with which it’s most often paired and compared. Logistically, sourcing microlots here (and getting them out of the country) is difficult: It’s a landlocked country, one of the poorest in the world, and still burdened by a history of political unrest thanks to a brutal colonial history and the aftershocks that will, like any colonial history, be felt for generations to come.

The coffee, though? It’s worth it.

Every year, we await Burundi coffees with giddy anticipation: The best of them are often stunning, pushing the highest reaches of our cupping scores. These are sugar-fruit coffee: fig jam, floral, sparkling with citrus. Before anyone thought to seek out (and pay for) specialty coffees from here, however, these lots were lost in bulk, commercial exports. Jason A. Long, Café Imports head of sourcing and CEO, was one of the first champions of Burundi as a specialty-coffee origin to watch, and he remains dedicated to discovering and bringing to market the microlots with the most character, structured acidity, and, yes, plenty of sparkle.

HISTORY

Coffee production has been something of a roller coaster in Burundi, with wild ups and downs: During the country’s time as a Belgian colony, coffee was a cash crop, with exports mainly going back to Europe or to feed the demand for coffee by Europeans in other colonies. Under Belgian rule, Burundian farmers were forced to grow a certain number of coffee trees each—of course receiving very little money or recognition for the work. Once the country gained its independence in the 1960s, the coffee sector (among others) was privatized, stripping control from the government except when necessary for research or price stabilization and intervention. Coffee farming had left a bad taste, however, and fell out of favor; quality declined, and coffee plants were torn up or abandoned.

After the civil war–torn 1990s and the nearly total devastation of the country’s economy, coffee slowly emerged as a possible means to recover the agrarian sector and increase foreign exchange. In the first decade of the 2000s, inspired in large part by neighboring Rwanda’s success rebuilding through coffee, Burundi’s coffee industry saw an increase in investment, and a somewhat healthy balance of both privately and state-run coffee companies and facilities has created more opportunity and stability, and has helped Burundi establish itself as an emerging African coffee-growing country, despite its small size and tumultuous history.

Like Rwanda and, to a lesser extent, Democratic Republic of Congo, Burundi battles the infamous “potato defect,” a microorganism that contributes a raw-potato-like flavor and aroma to infected beans, and which can’t be detected by sight in parchment, green, or roasted coffee. Research efforts to eradicate the defect completely have shown promise, and we look forward to the day when the potato is a distant memory.

MICROLOTS

Like many of its neighbors in Africa, Burundi produces microlots almost by default: Each farmer owns an average of less than even a single hectare, and delivers cherries to centralized depulping and washing stations, SOGESTALs (Sociéte de Gestion des Stations de Dépulpage Lavage), and it may take more than producers’ delivery in order to create a lot.

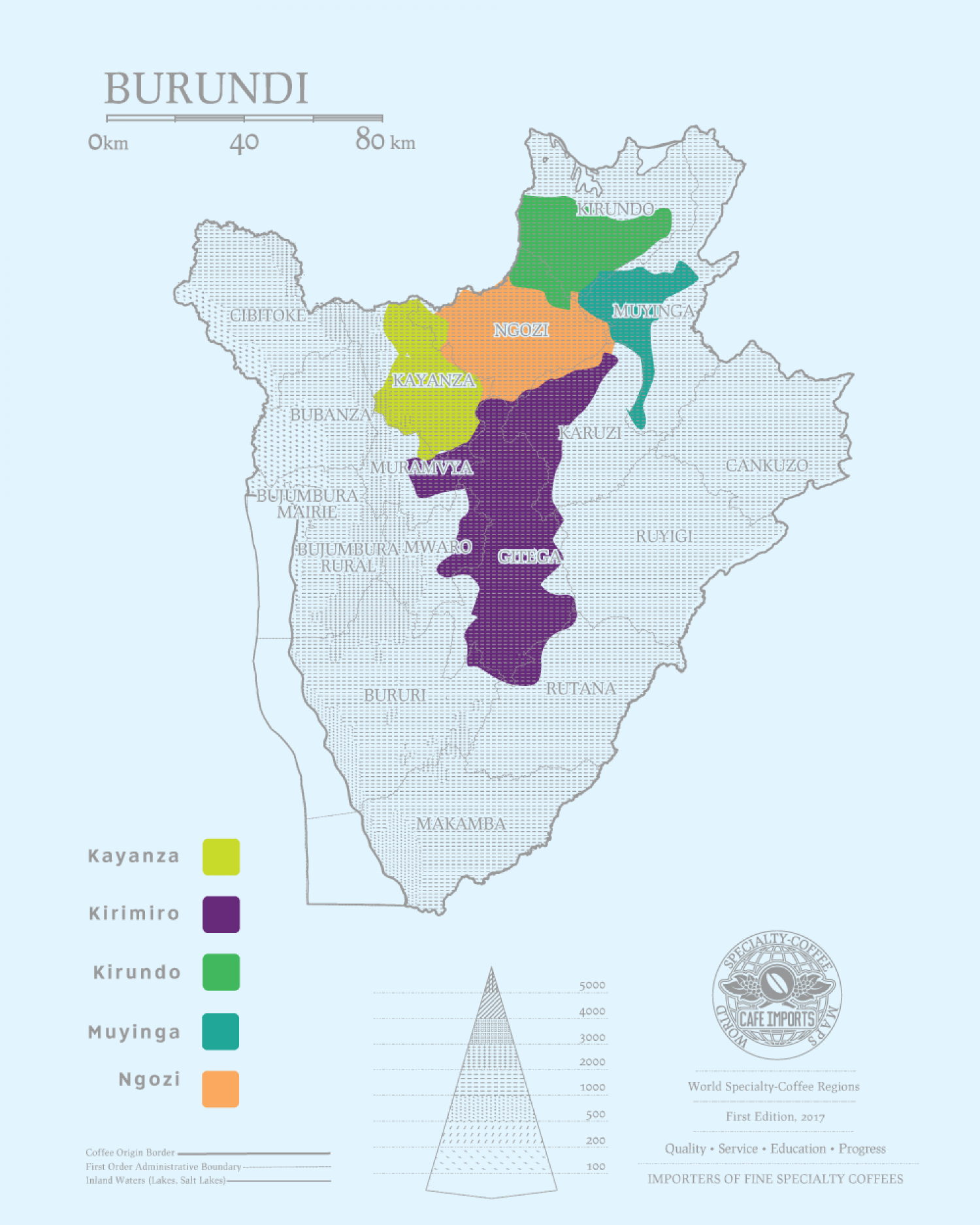

This purchasing style makes it nearly impossible, if not completely impossible, to arrive at single-producer, single-farm, or single-variety lots; instead, coffees are typically sold under the appellation of the washing station. (In Kayanza, there are 21 washing stations, including familiar names to Cafe Imports’ offerings page: Gackowe, Butezi, Gatare, and Kiryama.)

Depending on the leadership and management at the stations, both private- and state-run, the attention to detail in the processing makes a big difference, with meticulous sorting, fermenting, and washing necessary to create quality and uniformity among the coffee. The typical processing method in Burundi is similar somewhat to Kenya, with a “dry fermentation” of roughly 12 hours after depulping, followed by a soak of 12–14 hours in mountain water. Coffees are floated to sort for density, then soaked again for 12–18 hours before being dried in parchment on raised beds.