CAFE IMPORTS + COLOMBIA

For us at Cafe Imports, there’s something about Colombia.

Actually, there’s not “something” about Colombia, but many, many somethings that make this place particularly special among coffee-growing countries, and as famous. Everyone knows Colombian coffee—or thinks they do. However, to simply say a coffee is from Colombia is to tell just a fragment of the story, like recommending a book to a friend by only telling her the name of the publisher. To really get to know Colombian coffee is to travel thousands of miles, taste through thousands of cups, and wear out dozens of pairs of hiking boots touring hundreds of coffee farms from north to south. Even that’s just the beginning—but every beautiful story needs a beginning.

We have had boots on the ground (and spoons in the cup) here since our earliest days, and we fall in love over and over again with the regional variations, the varieties, the landscape, the producers themselves. From our work sourcing strong, versatile workhorse coffees for our Excelso Gran Galope signature offerings; to our celebration of the taste of place with Regional Selects from Cauca, Huila, Nariño, and Tolima; to the discovery and development of microlots from all over the country with our export partners and the producers with whom they work closely—we simply can’t get enough.

Neither can our customers: Our offerings sheet comprises a wide selection of flavors, farms, and terroirs, and we will continue to explore new-to-us regions and to support the mostly smallholder farmers of Colombia into the future, as long as they’ll keep letting us come back again and again and again.

HISTORY

Coffee came to Colombia in the late 1700s by way of Jesuit priests who were among the Spanish colonists, and the first plantings were in the north of the country, in the Santander and Boyaca departments. Throughout the 19th century, coffee plants spread through the country, with a smaller average farm size than more commonly found throughout other Latin American producing countries.

Commercial production and export of coffee started in the first decade of the 1800s, but remained somewhat limited until the 20th century: The 1927 establishment of the Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia (aka FNC, see below) was a tremendous boost to the national coffee industry, and Colombia quickly established itself as a major coffee-growing region, vying with Brazil and Vietnam for the title of top global producer.

Colombia still produces exclusively Arabica coffee, and though the country suffered setbacks and lower yields from an outbreak of coffee-leaf rust in the early 2010s, production has fairly bounced back thanks to the development and spread of disease-resistant plants, as well as aggressive treatment and preventative techniques.

REGIONALITY

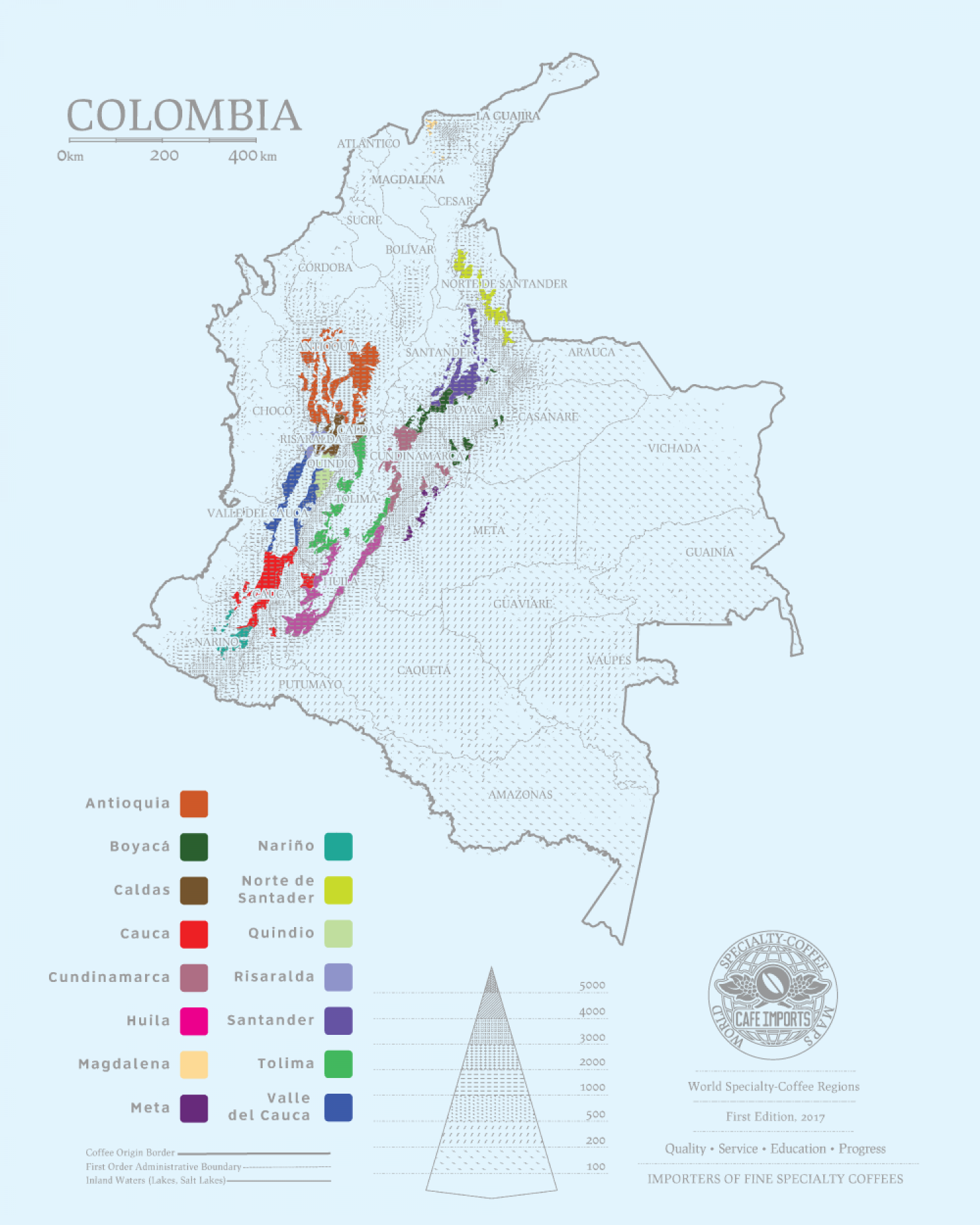

Colombia’s size alone certainly contributes to the different profiles that its 20 coffee-growing departments (out of a total 32) express in the cup, but even within growing regions there are plentiful variations due to the microclimates created by mountainous terrain, wind patterns, proximity to the Equator, and, of course, differences in varieties and processing techniques.

The country’s northern regions (e.g. Santa Marta and Santander) with their higher temperatures and lower altitudes, offer full-bodied coffees with less brightness and snap; the central “coffee belt” of Antioquia, Caldas, and Quindio among others, where the bulk of the country’s production lies, produce those easy-drinking “breakfast blend” types, with soft nuttiness and big sweetness but low acidity. The southwestern departments of Nariño, Cauca, and Huila tend to have higher altitude farms, which comes through in more complex acidity and heightened florality in the profiles.

To capitalize on this broad spectrum of flavors and to emphasize the diversity available to roasters and consumers from within a single country, the coffee growers’ association has begun to provide origin distinctions, and has developed aggressive marketing campaigns designed to boost the regions’ signals to buyers worldwide.

NATIONAL FEDERATION OF COFFEE GROWERS

Founded in 1927, the Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia (aka the National Federation of Coffee Growers, hence the “FNC” abbreviation) is a large NGO that provides a wide variety of services and support to the country’s coffee producers, regardless of the size of their landholdings or the volume of their production. The marketing arm of the FNC develops campaigns to push not only international consumption of Colombian coffee, but also, more recently, domestic consumption of specifically specialty-grade Colombian coffees. (The creation of the Juan Valdez “character” in the 1950s is the clearest example of the outward-facing advertising that has built the FNC’s reputation; the creation and spread of Juan Valdez cafes in-country continues the institution’s mission to grow domestic consumption as well.)

The FNC also guarantees a purchase price for any coffee grown within Colombia, which provides some degree of financial security to farmers: They have the option to find private buyers or break into specialty markets, or they can tender their coffee to the FNC and receive a somewhat stable (if also rather standard, influenced by the global commodities market) price at any point during the year. This is designed to eliminate some of the market pressures and provide reliable income to the coffee sector, though it also comes under criticism for disincentivizing the development of super-specialty lots and microlots.

The scientific arm of the organization, Cenicafé, is devoted to research, development, dissemination, and support throughout the country. A wide-ranging extension service employing more than 1,500 field workers is deployed to meet and consult with farmers on soil management, processing techniques, variety selection, disease prevention and treatment, and other agricultural aspects to coffee farming. A tax is imposed on all coffee exports in order to fund this work as well as the other provisions and protections that the FNC offers, regardless of a producer’s participation or use of FNC services, marketplace, and programs.

The FNC also built and operates a coffee theme park in Quindío (Parque Nacional del Café), in collaboration with the Department Committee of Coffee Growers of Quindío: In it is a coffee-history museum, a coffee garden, an example of a traditional farmer’s house, and a roller coaster called “La Broca.”