CAFE IMPORTS + ECUADOR

When Café Imports bought its first half-container from Ecuador in 2012, we were the first company to export specialty coffees from Pichincha, an emerging growing region north of Quito. Two years later, when the Arabica exports dropped down to 30 containers, Café Imports bought three of them—10 percent of the national total!

Low production and low incentives for growers are among the challenges to sourcing and buying fine coffees from Ecuador: The logistics involved in filling a container can be frustrating, but with time and investment in the relationships we’ve begun there, we are confident that there will be more and more cups hitting the upper scores on our sensory table in coming years.

Café Imports’ senior green-coffee buyer Piero Cristiani has spent several years really actively seeking, nurturing, and maintaining relationships with growers in this country, and he has come to very strongly believe in the potential to uncover and even assist in the development of more and more 90+ point microlot coffees, as well as some larger Regional lots over time. We look at the future of Ecuador’s fine-coffee industry with very optimistic eyes—and cups!

HISTORY

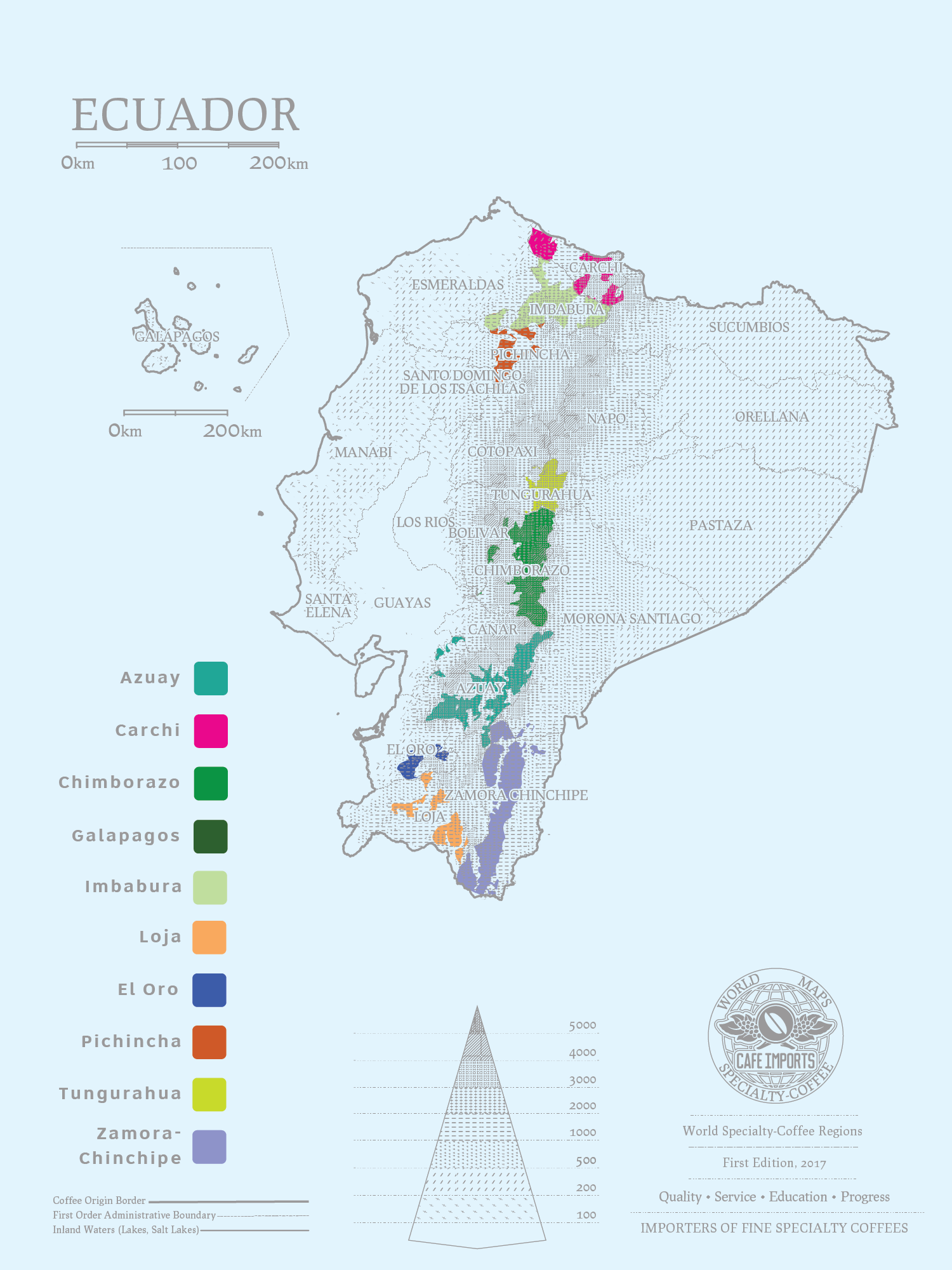

Coffee came to Ecuador in the middle of the 19th century, planted in the low-altitude region of Manabi, which ranges from 500–700 meters. The region is still the largest area for Arabica production, producing about 50 percent of the country’s Arabica yield, though better-quality Arabica can be found elsewhere, at higher elevation.

Coffee didn’t become a major commercial venture in Ecuador until the late 1920s, when the cacao industry was threatened by disease—even then, coffee has largely remained an afterthought to the national economy, and production dropped greatly during the price crises of the 1990s and in the early 2000s. Ecuador’s economy is largely reliant on petroleum, and less so on agriculture than many other coffee-growing countries. (Another somewhat strange fact about Ecuador’s coffee industry is that the country imports more than it grows or sells: A large soluble-coffee industry demands that very inexpensive Robusta be purchased from Vietnam to meet domestic consumption needs, while Ecuadorians sell their own green Robusta to nearby coffee-producing countries (like Colombia) at a higher price for their instant-coffee use.)

The country’s elevation ranges from sea level all the way to above 2,000 meters—a wide-ranging difference of terrain and climate that, combined with the specific challenges equated with its location on the Equator, provide a unique—but not impossible to overcome—challenges. Selective harvesting is especially difficult: Due to the country’s location on the Equator, the coffee needs to be harvested throughout the year. A branch will often contain all stages of the coffee’s developmental cycle in one: green coffee, ripe coffee, and blossoms side by side. This forces a farmer to hold some coffee, while processing and harvesting enough for export, and it also leads to higher labor costs due to the extended picking cycle.

Another significant challenge is climate change. Since this country is prone to such delicate shifts in weather due to the altitude and Equator, jungle to the east and ocean to the west, slight climatic changes have a huge impact on the farmland. Areas that are used to seeing fog in the mornings and sun in the afternoon are now shrouded in fog all day long, which prevents even drying on patios. Farms that have been accustomed to a lot of sun in some cases are seeing temperatures and exposure rise too high and the climate too try to produce the same quality as in previous years. Adaptation is a must for farmers here.

Starting in the first decade of the 2000s, however, the specialty boom happening in neighboring Colombia and even in northern Peru inspired entrepreneurial coffee producers to invest in good Arabica varieties, improved practices—picking ripe and better processing, rather than simply letting the coffee dry on the tree as café en bola, the traditional method—and advanced marketing strategies. Increasingly, single-farm, single-variety, and innovating processing lots are finding their way to forward-thinking mills, exporters, importers, and roasters.

THE PROMISE OF SIDRA

One of the most interesting developments to happen in Ecuadoran soil is the appearance of a new cultivar, called Sidra. A cross between a Bourbon and a Typica variety (themselves genetically relatively closely related), these coffees can express a very unique fruity, floral characteristics. When grown at higher altitudes and processed meticulously, these coffees stand out on the cupping table, and have the potential to bring Ecuador into the spotlight as a specialty-producing country.