You’re joining Victor (Marketing Manager), Kate (Senior Supply Chain Specialist), Devon (Sustainability & Stakeholder Engagement), and our indefatigable green buyer in Africa, Claudia, for a visit with some old friends and some new ones as we explore the reaches of both culture and cup in Rwanda.

But first, we need to start this tale off with some reflection. Rwanda has stood as a shining example of peace and community restoration in the wake of the horrific events during the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi. Walking the grounds of the memorial in Kigali, it’s hard to imagine that just a few short months later, violence would once again rock the fragile boat of stability between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo[1]. Looking back on our time there and the people we met who have dedicated their lives to building a better future for Rwanda, we’re grateful and hopeful that the same compassion that healed unimaginable wounds in the past will prevail once again today.

Rwanda has a tenuous history with coffee. In a land of subsistence farming, the introduction of coffee was both an opportunity and a curse when the Germans brought it with them in the early 1900s during Rwanda’s first colonial rule. After Rwanda was ceded to the Belgians post World War I, the commercialization of coffee production ramped up to meet demand in Belgium and specifically Switzerland (still the largest importer of Rwandan coffee to this day). Production grew over the next fifty years and became a substantial part of Rwanda’s overall GDP, with farmers growing both subsistence crops and coffee (something celebrated on their currency!), but often not on the same lands due to restrictions put in place by the Belgians on the use of fertilizer for growing crops other than coffee or tea. This put farmers at a distinct disadvantage by limiting their production of food crops and cattle, leading to reliance on other income sources like working for commercial farms.

Up until the 90’s, about 80% of Rwandans worked in agriculture, mostly in commercial coffee and tea, as they offset the ever-decreasing subsistence yields and income from their own farms. This changed drastically with the collapse of the International Coffee Agreement (ICA) in 1989, which saw coffee prices spiral and fluctuate wildlyfrom $1.32 to $0.77 over the next five years (until 1994). It would be a stretch to say that the post-ICA crash directly led to the genocide against the Tutsis of 1993/94, but it certainly drove an already deeply disadvantaged group of the Rwandan people further into poverty and desperation [2][3].

After those horrific events, and on the way to becoming a global beacon for hope and peace, the coffee industry in Rwanda was turned completely around. Post genocide, about 90% of the population turned to subsistence agriculture for survival. This renewed reliance on domestic food production, focus on social and political equality, and an easing of taxes and restrictions on farm inputs fostered international investment by aid groups, academia, and industry, leading to the construction and standardization of Coffee Washing Stations (CWS) and the fundamental shift in focus from commercial coffee to the beautiful specialty coffees we know and love today [4][5].

You’ll hear it repeated by farmers as you wind your way across the landscape, pinned above the entrance as a welcome in the airport, and on the billboards around Kigali, but “The land of a thousand hills” is no mere marketing slogan. Africa’s fourth-smallest mainland country is home to countless volcanic and water-hewn peaks and valleys. From the surface of Lake Kivu at 1,460m to the top of Mt. Karisimbi at 4,507m, this ruggedly carved landscape creates a vast array of microclimates and growing conditions across the main coffee-growing regions [6]. These coffee growing regions more-or-less fall within Rwandas provinces, which were drawn following the natural features in the landscape.

The Western Region sits along the shores of Lake Kivu, one of Africa’s Great Lakes, nestled within the western branch of the Great Rift Valley. This dramatic geological setting creates a unique microclimate where the lake’s moderating influence meets high-altitude growing conditions at around 1,463m elevation. The region’s volcanic soils, remnants of ancient tectonic activity, provide exceptional mineral content that contributes to rich soil fertility. Coffee here is the earliest to ripen in Rwanda, with harvesting beginning in late February on the lake shores. The region encompasses districts like Karongi, Rutsiro, and Nyamasheke, where small-scale farmers cultivate predominantly Red Bourbon varieties on terraced hillsides. The steep western slopes descending toward Lake Kivu and the Ruzizi River valley create a dramatic landscape that is both challenging for farmers and ideal for producing complex, high-quality coffees.

The Northern Region is also distinguished by its black volcanic soils derived from the chain of volcanoes in Rwanda’s northwest, creating some of the most nutrient-dense growing conditions in the country. The Virunga Mountains, part of the Albertine Rift, not only provide ideal terroir but also serve as home to Rwanda’s famous mountain gorillas, making this region significant for both coffee and conservation. In districts like Gakenke and Musanze, coffee is sometimes harvested as late as August, extending the harvest season considerably beyond other regions.

The Central Plateau, including the Kizi Rift area, forms part of Rwanda’s central uplands, where the divide between the Congo and Nile drainage systems creates a unique geographical position. This region has an average elevation of nearly 2,700m along the drainage divide, though coffee is grown at the more moderate elevations on the slopes below. The plateau represents a transition zone between the dramatic western slopes and the gentler eastern terrain characterized by the rolling hills that have earned Rwanda its nickname as the “Land of a Thousand Hills.” The central areas benefit from Rwanda’s temperate highland climate despite being only two degrees south of the Equator, with temperatures moderated by elevation.

The Eastern Region, encompassing areas around Lake Muhazi and extending toward Akagera, represents a more moderate landscape where the central uplands slope gradually eastward at progressively lower elevations toward the plains and wetlands of the eastern border. Districts like Kayonza, Ngoma, and Kirehe grow coffee at elevations typically between 1,200 and 1,700 meters. While less dramatic in elevation than the western or northern regions, the Eastern Plateau benefits from the eastern savannah climate with slightly moderated rainfall patterns. This region has seen significant agricultural development in recent decades, with coffee often grown alongside other crops in Rwanda’s characteristic small-farm systems. The eastern areas also benefit from their proximity to major transport routes, making coffee processing and export logistics somewhat simpler than in the more remote mountainous regions.

The Southern Region has become synonymous with complexity and diversity in Rwanda’s specialty coffee scene, famous for producing coffees with intricate flavor profiles featuring red fruits, caramel, and spicy notes. Districts like Huye and Nyamagabe sit on the central plateau, where rolling hills create varied microclimates and the elevation provides ideal growing conditions for Bourbon. This region played a pivotal role in Rwanda’s post-genocide coffee renaissance, as many of the country’s first specialty coffee washing stations were established here with international support. The southern areas benefit from consistent rainfall patterns during the two rainy seasons (February–May and September–December) and well-draining soils that allow coffee to thrive. Culturally, the southern region represents the heart of Rwanda’s transformation from producing commercial coffee to becoming a recognized specialty coffee origin, with many cooperatives and washing stations serving as models for quality-focused production throughout the country.

You might recognize a few of the places we’re spotlighting on this journey as old-time favorites, but we’ll mix in some future classics as well. Kibirizi, Kigeyo, Kirorero, Cyato, Abadatezuka, Rulindo, are just a few of the washing stations we visited that make the most of the unique terroir found across Rwanda and are shining examples of community involvement.

Since Cafe Import’s CEO Jason Long first met COOPAC and started sourcing from Rwanda around 15 years ago, we’ve searched for new and interesting coffees and partnerships as the specialty focus has grown here. Innovations in processing and new models to promote sustainability for the roughly 400,000 smallholder families that rely on coffee are taking hold, and the results are truly inspiring.

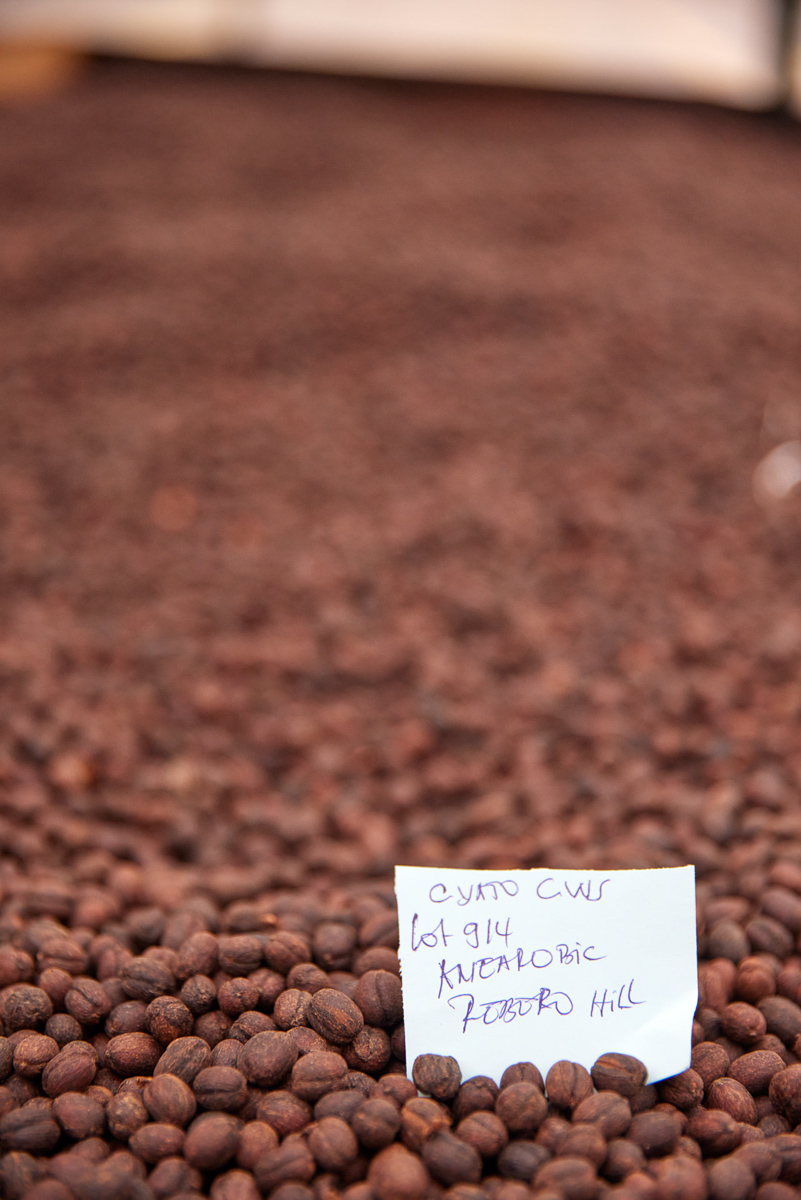

Our first stop is the Karundura Valley, which sits between Nyungwe Forest National Park and the southeast shore of Lake Kivu. Wind your way a couple of hours straight up seemingly impossibly steep and muddy jungle roads from the lake, and you’ll find the Cyato coffee washing station (CWS), nestled on the valley wall at ~1900m. One of three washing stations operated by Tropic Coffee, Cyato was built in 2017 to process the coffees of nearby farms, provide a space for processing experiments, and a platform to start their youth and women’s social programs. As Kate observed, while the tires of the Land Cruiser howled trying to find grip on yet another mudslick log in the road on the way down, the timing between rains is everything for moving coffee in and out of these remote areas. It’s one of the many challenges that come with sourcing coffee in landlocked countries.

Like most washing stations in Rwanda, they buy coffee in cherry from farmers in the surrounding area, which is hand sorted by color for ripeness, cupped, combined based on quality, or separated out as micro-lots. Cyato is fully equipped to produce washed, honey, natural, and anaerobic coffees, which, after processing, are dried on raised beds, either out in the open or in the greenhouse that was recently built onsite. Each lot, no matter how big or smallundergoes multiple quality control cuppings at the washing station and the Tropic cupping lab in Kigali.

You can tell owners of Tropic Coffee, Chris and Divine, are really proud of the innovation happening at Cyato. Chris, with a background in agro-climatology, and Divine, with the detail-oriented mindset that comes from studying computer science, have turned Cyato into an efficient space for eking out every last bit of character from the coffees processed here.

Much of that coffee comes from farms within walking distance of the station, including the nearby village of Abadatezuka. Formalized as a Cooperative in 2019, the Abadatezuka group has been together informally since 2014. If you’re used to the term “Coop” in terms of the groups of farmers commonly seen in Central and South America, you’d find the groups here to be structured similarly. The term “Cooperative” was formalized around 2007 by the government of Rwanda to provide a legal and statutory framework for these groups of farmers who were already pooling their resources. This codification unlocked access to national and international assistance, such as the Partnership for Enhancing Agriculture in Rwanda (PEARL), technical assistance, health insurance for members, access to loans, quality premiums, and access to farm inputs. Something the farmers of Abadatezuka pointed out as a huge benefit they’ve seen since forming the Coop and working with Tropic the last few years.

Abadatezuka village itself sits just down the ridge from Cyato CWS, and we were welcomed by the leadership of the coop (both women and men), and a large portion of the Gwiza Women’s Group, which is now about 75 members strong. The group grows, processes, and sells their coffee in microlots, which include a gender equity price premium. As with many farms in Rwanda, the farmers here grow the Bourbon variety, underplanted extensively with nitrogen-fixing crops like legumes, Irish potato, gourd, and sorghum. The average farm is only about 1 hectare per person, so growing multiple crops at once is crucial, providing multiple sources of both income and food. This can be a challenge at some of the higher farms that border Nyungwe National Park at 2200+ meters, making the tools and skills for maintaining consistent plant health and alternative fertilizer sources from vermiculture provided by Tropic, key resources.

Strolling (or rather scrambling) along with Vincent up-valley from Cyato, we’re greeted with a crash from the storm looming overhead. Though his family has grown coffee for generations, Vincent has been growing coffee in earnest since 1989 and began to explore methods to increase both volume and quality in partnership with Tropic. This focus on consistent quality has built a solid foundation for anaerobic processing at Cyato and is one of our favorite microlot offerings.

The views and sounds you experience on the hike to the farm are not quite your typical hiking experience. The Kivu region has a history of coltan speculation mining, which is a source of Tantalum used in capacitors, glass lenses, and is used extensively by the defense industry in missile guidance systems and jet engines. Many of these mines on the Rwanda side of the lake have been abandoned and are now considered to be “artisanal” mines. That is to say, the scars in the landscape are used by locals who now extract the valuable ore by hand. Between the threat of landslides and the health impacts of handling the material, it’s a risky business, but can be a source of income for those who don’t have access to land [7].

We saw this firsthand while visiting Vincent. His farm is a beacon of hope amongst a landscape marred by one of these mines, and though the mine has been abandoned, the locals continue to extract coltan by hand. As we chatted with Vincent, the valley echoed with thunder as a wall of mud and debris swept through ahead of the coming rain. It’s a stark reminder of why, after three generations of coffee growing before him, he continues to work towards improving the farms.

“I hope to continue [growing coffee] and expand my lands so that I can provide for my children. I have one in university and want to send the rest so they do not have to work mining” ~Vincent Rukeribuga

It’s Tropic’s hope that the programs they have built can provide the land, knowledge, and resources to provide people with an alternative safe option to working the old mines and prevent further encroachment of deforestation into Nyungwe National Park. Critical as the cost and availability of fertilizers and farm implements rise, and land for growing is limited.

Until March of 2023, farms in Rwanda were grouped into Zones and were required to sell their coffee to a CWS within their designated zone. This ensured that the washing stations would receive a steady supply of cherry and stabilized pricing, allowing them to offer pre-harvest financing and farm management support to foster quality. This paradigm changed when the Rwandan Ministry of Agriculture and Animal Resources repealed this zoning policy, opening the door for free-market trade between different zones. For 2024, the National Agricultural Export Development Board (NAEB) set the minimum price for coffee in cherry at RWF410/kg or $0.70/lb, but the actual price paid by now-competing washing stations is often much higher (in 2023 avg RWF650/kg), addressing some of these income limitations that can prevent farmers from thriving [4].

“We started these programs to provide an alternative and support. It gets youth away from the mines and women another way to provide for their families” – Tropic Coffee

A rhythmic chanting fills the night sky, and the screeching of a fish eagle punctuates an already eerily calm night on Lake Kivu. Was that actually a bird? Or could it have been the first victim of a so-called “limnic eruption” I’ve read about? One of three lakes in the world that has the potential to see this phenomenon, subaquatic volcanic activity has created vast reserves of methane in the lake depths that could find their way to the surface, “erupting” and wiping out anything that breathes, coffee travelers included [8][9].

Thankfully for the moment this deadly potential is being used to bring power to the lakes’ residents and fueling a boom in the electrification of once diesel-powered industries, such as coffee processing. Commissioned in 2016, the KivuWatt power station utilizes the lake’s methane stores to provide around 30% of Rwanda’s energy needs, sitting on the lake’s surface as an example of innovation and international investment [10].

Myths and lore abound around the creation of this iconic body of water that marks a fluid border between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Nearly 500m deep and created by the separation of two tectonic plates being ripped apart by volcanic activity since at least the early Holocene period, its rugged shores and slew of small islands are a sight to behold as we crest the pass coming down from Virunga National Park. The volcanic activity, lake-driven microclimate, and network of small ports on both sides of the border have made the waters and shores of the lake both incredibly fertile and a bustling place for fishing and coffee trade [11].

COOPAC has made a substantial investment in washing stations here. Founded by the current organization president Emmanuel Rwakagara in 2001 alongside around 110 other farmers who wanted to work towards higher-quality coffees while minimizing environmental impact and building social programs for their membership, COOPAC is our longest-standing partner in Rwanda. Fast forward to today, and they’ve grown to six washing stations with 8,000 members and counting. Farmer support programs are still core to their mission. Providing agronomic and quality improvement training, fertilizers and farm inputs, and community support through the construction of schools and infrastructure, COOPAC has been key to shaping coffee in Rwanda.

Exploding lakes and the morbid comedy that comes with a vision of suffocating in a cloud of cow farts (I grew up in a ranch town, methane = cows to me), leave the mind as we step into a launch that will take us south down the lake to visit Kirorero washing station. Cutting through the waves offshore gives us a completely new perspective on the scale of this basin that has been carved for eons. Looking back towards shore, we spot the steep valleys that lead down from some of the washing stations perched higher up on the wall that we visited earlier in the day.

Kabirizi and Kigeyo washing stations are perhaps the most iconic, and you may recognize them as long-standing favorites. Both washing stations are perched in the forest on a steep slope about 300m above the lake and receive coffee from around 1000 farmers every harvest. Most of the farms are uphill, which shortens the harvest from late February to early May. Like other COOPAC washing stations, processing here is mostly a three-stage washed, taking 20-25 days from cherry to bagged and ready for export.

Chatting with Fabien Kayober, who manages Kibirizi, about hopes for the upcoming harvest season, he reminds us that the environment here is a constant factor that they must consider, but they are always seeking to innovate.

We hope to work towards more certifications. We have nice quality coffee, but can always improve” ~ Fabien Kayobera

Back in the launch, it’s getting choppy, making progress down the lake slow as steel blue storm clouds gather on the horizon. We spot a group of men waving from shore with an array of raised beds unfolding up the valley behind them. Kirorero is a unique and stunningly beautiful place. Tucked in the steep walls of the Gasuma valley right at the shoreline, Kirorero receives coffee from around 1500 farmers that deliver cherry primarily by boat, foot, or bicycle.

Since the washing stations does not have direct access via a solid road, processed coffee is moved on the water up to Nyamwenda washing station before being loaded on trucks to make the long trek up to the nearest paved road that runs above the lake. From farm to boat to processing, to boat, to truck, to rail, to ship, to rail, to finally landing in our warehouse; It’s a supply chain that exemplifies the many people and connections it takes to make coffee work.

This commitment to the development of the cooperative as a whole is a common thread amongst the folks at COOPAC. Echoed by Nyawenda washing station manager Marcel Twizerimana when asked about why he took on the role.

“I became this station’s manager for the experience, I wanted to get to know the farmers [here] and understand the unique issues they face to be able to do more about them” ~ Marcel Twizerimana

There’s a flurry of activity as everyone eyes the skym preparing for the imminent deluge by quickly covering up the coffee basking in the cool breeze on raised beds. It’s looking like it’s probably time to say goodbye to this unique place and jump in the launch for the trip back to port before the storm truly sets in. We shake hands and cast off before hugging the coastline north as fishermen in amakororo (a three-hulled canoe) return home after delivering the night’s sambaza (a small sardine-esque fish that is a local staple and absolutely delicious) catch, battling the wind using arm and paddle power. Gishamwana and the hundreds of other little islands that dot the lake, each with their own story beckoning to be told, call to us as places of immense beauty, fascinating history, and for the moment, a complicated future.

Rwanda is a place balancing respect for tradition with a renewed wave of investment, development, and demand from around the globe. In Kigali, this is punctuated by towering cranes hoisting glass facades onto shiny new bank buildings, and the hum of electric cars from China offsetting the deluge of motorcycle exhaust. In rural area,s it’s often the humble bicycle carrying both farmer and harvest (occasionally a fridge or bed frame) to and from the farm; a cornucopia that must provide both nutrition and income for a growing family on ever-shrinking land area. These two worlds colliding have opened the door of opportunity and the challenges that come with it.

From the incredible attention to detail and experimentation we saw with Tropic, to the long-term community impact and stability achieved by COOPAC, this is just a small slice in the evolutionary timeline of coffee in Rwanda. The proliferation of Coffee Washing Stations may have transformed the coffee industry here in terms of processing, but it’s the generations of knowledge and experience caring for small plots of land (Rwanda is the most densely populated country on mainland Africa) in harmony with local ecosystems that have laid the foundation for the delicious coffees we love and enjoy today.

Try some of our favorite coffees from Rwanda this year, fresh crop arriving soon to a Cafe Imports near you.

1. Conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo

https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/violence-democratic-republic-congo

2. The political economy of coffee, dictatorship, and genocide

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0176268002001660

3. Lessons from the world coffee crisis: A serious problem for sustainable development

https://www.ico.org/documents/ed1922e.pdf

4. National Agricultural Export Development Board (NAEB)

https://www.naeb.gov.rw/rwanda-coffee/about-rwanda-coffee

5. Partnership for Enhancing Agriculture in Rwanda through Linkages (PEARL) – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Partnership_for_Enhancing_Agriculture_in_Rwanda_through_Linkages#:~:text=This article is about an,on coffee and cassava products.

6. GIS-Based Multi-Criteria Analysis for Arabica Coffee Expansion in Rwanda

7. What coltan mining in the DRC costs people and the environment –https://theconversation.com/what-coltan-mining-in-the-drc-costs-people-and-the-environment-183159

8. Troubled waters: life on the edge of Africa’s Lake Kivu – in pictures

9. Nasa – A Sudden Color Change on Lake Kivu

https://science.nasa.gov/earth/earth-observatory/a-sudden-color-change-on-lake-kivu-87931/

10. Contour Global – KivuWatt

https://www.contourglobal.com/assets/kivuwatt/

11. Soil Fertility in relation to Landscape Position and Land Use/Cover Types: A Case Study of the Lake Kivu Pilot Learning Site

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/2015/752936

12. Spatial variability of seasonal rainfall onset, cessation, length and rainy days in Rwanda