CAFE IMPORTS + COSTA RICA

Since Cafe Imports bought its first container of Costa Rican microlots at the end of the 2006/2007 harvest, the country has become a model for other buying relationships around the world. The ability for a producer to separate top lots from more standard coffees; sell the lots at corresponding, appropriate prices; and gain individual recognition for their work and quality, has had a rippling effect among the communities from which we source, and the response has been tremendous. Every year, more producers express an interest in improving the picking, sorting, and processing they do on the farm level in the hopes of earning better prices and achieving a level of market visibility.

While we have a core set of partners—with micro-producers as well as co-ops—whose coffees are the standard-bearers for our Costa Rica offerings year by year, we are always meeting new producers and creating connections that result in some of the most exciting, innovative, and certainly delicious coffees that the country has to offer.

HISTORY

Coffee was planted in Costa Rica in the late 1700s, and it was the first Central American country to have a fully established coffee industry; by the 1820s, coffee was a major agricultural export with great economic significance to the population. National output was greatly increased by the completion of a main road to Puntarenas in 1846, allowing farmers to more readily bring their coffee from their farms to market in oxcarts—which remained the way most small farmers transported their coffee until the 1920s.

In 1933, the national coffee association, Icafe (Instituto del Café de Costa Rica), was established as an NGO designed to assist with the agricultural and commercial development of the Costa Rican coffee market. It is funded by a 1.5% export tax on all Costa Rican coffee, which contributes to the organization’s $7 million budget, used for scientific research into Arabica genetics and biology, plant pathology, soil and water analysis, and oversight of the national coffee industry. Among other things, Icafe exists to guarantee that contract terms for Costa Rican coffee ensure the farmer receives 80% of the FOB price (“free on board,” the point at which the ownership and price risks are transferred from the farmer/seller to the buyer).

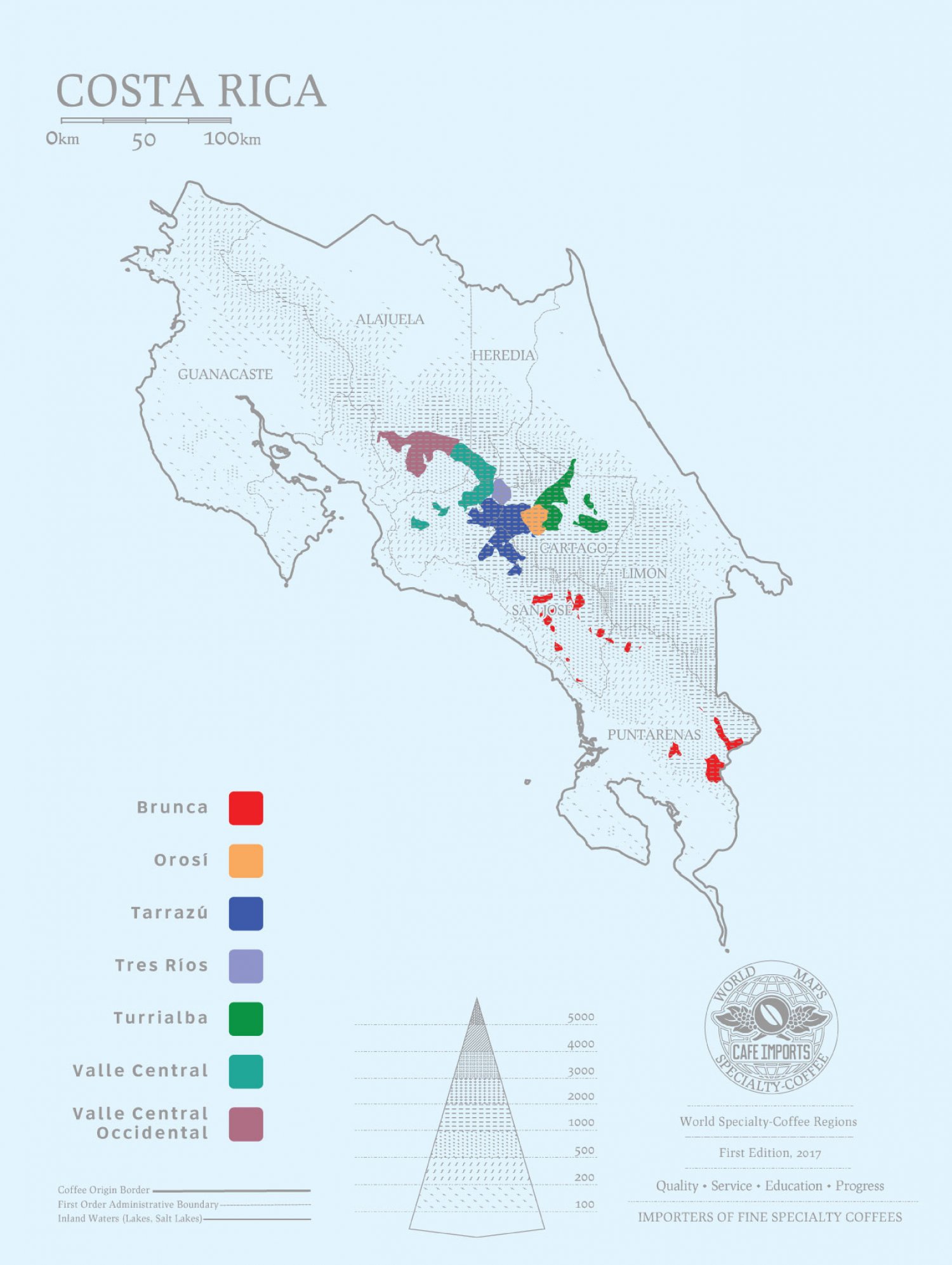

Costa Rica contributes less than 1% of the world’s coffee production, yet it has a strong reputation for producing relatively good, if often mild quality. One way that Costa Rica has hoped to differentiate itself among coffee-growing nations is through the diversity of profiles in its growing regions, despite the country’s relatively small geographical size. Tarrazú might be the most famous of the regions: Its high altitudes contribute to its coffees’ crisp acidity. West Valley has a high percentage of Cup of Excellence winners, and grows an abundance of both the Costa Rica–specific varieties Villa Sarchi and Villa Lobos, as well as some of the more “experimental” varieties that have come here, such as SL-28 and Gesha. Tres Ríos coffee has a smooth, milder profile—perhaps more “easy drinking” with toffee sweetness and soft citrus than the more complex or dynamic Costas available. Central Valley has some of the most distinct weather patterns in the country, with well-defined wet and dry seasons: We have found some of the best natural processed coffees in this region.

In recent years, coffee producers are increasingly interested in using variety selection as another way to stand out in the competitive market: SL-28 and Gesha are becoming more common, and local varieties like Villa Sarchi (a dwarf Bourbon mutation found near the town of Sarchi) and Venesia (a Caturra mutation).

MICROMILLS

Another development that has helped Costa Rican coffee producers differentiate themselves is the proliferation of micromills, or private wet- and sometimes dry-milling facilities that individual producers or groups of smallholders will build in order to control the processing and lot separation of their coffees. By investing in equipment such as depulpers or demucilaging machines, producers can harvest, depulp, and process their coffees in a variety of ways without relying on third-party mills, which can cut down on operating costs as well as increase the asking price for coffees.

PROCESSING AND PREP

Micromills have also been at the forefront of the processing innovations that have put Costa Rican coffees in the spotlight over the past decade: Honey processing, a kind of hybrid of a washed and pulped-natural process that originated in Costa Rica, has been more and more popular and prevalent among fine, lot-separated specialty coffees, though the term “honey” and its variations will vary from mill to mill based on their techniques. At some mills, the type of honey process (typically yellow, red, or black) is achieved by removing a certain percentage of the mucilage before the coffee is dried; other mills leave 100% of the mucilage on all their honey coffees, and instead modify the drying technique to create the various honey style.

Natural processing is also rising in popularity, in part because the profile can command higher prices, and because water restrictions can make fully-washed coffees more expensive and difficult to produce.

One of the Costa Rica–specific production details is that coffee here is measured by volume, rather than weight. Each mill has a receiving area, where cherry is brought and deposited into metal boxes called cajuelas, or “trunks.” Twenty cajuelas equals roughly one fanega, which is the 100-pound unit of measure in which producer receipts are written.

When the cherry is picked ripe, the fruit is both bigger and heavier than if it is over- or underripe, which means it will take fewer cherry to fill a fanega, and will bring a higher overall price to the coffee farmer. The country produces an average of 1.8–2.2 million fanegas annually.