CAFE IMPORTS + ETHIOPIA

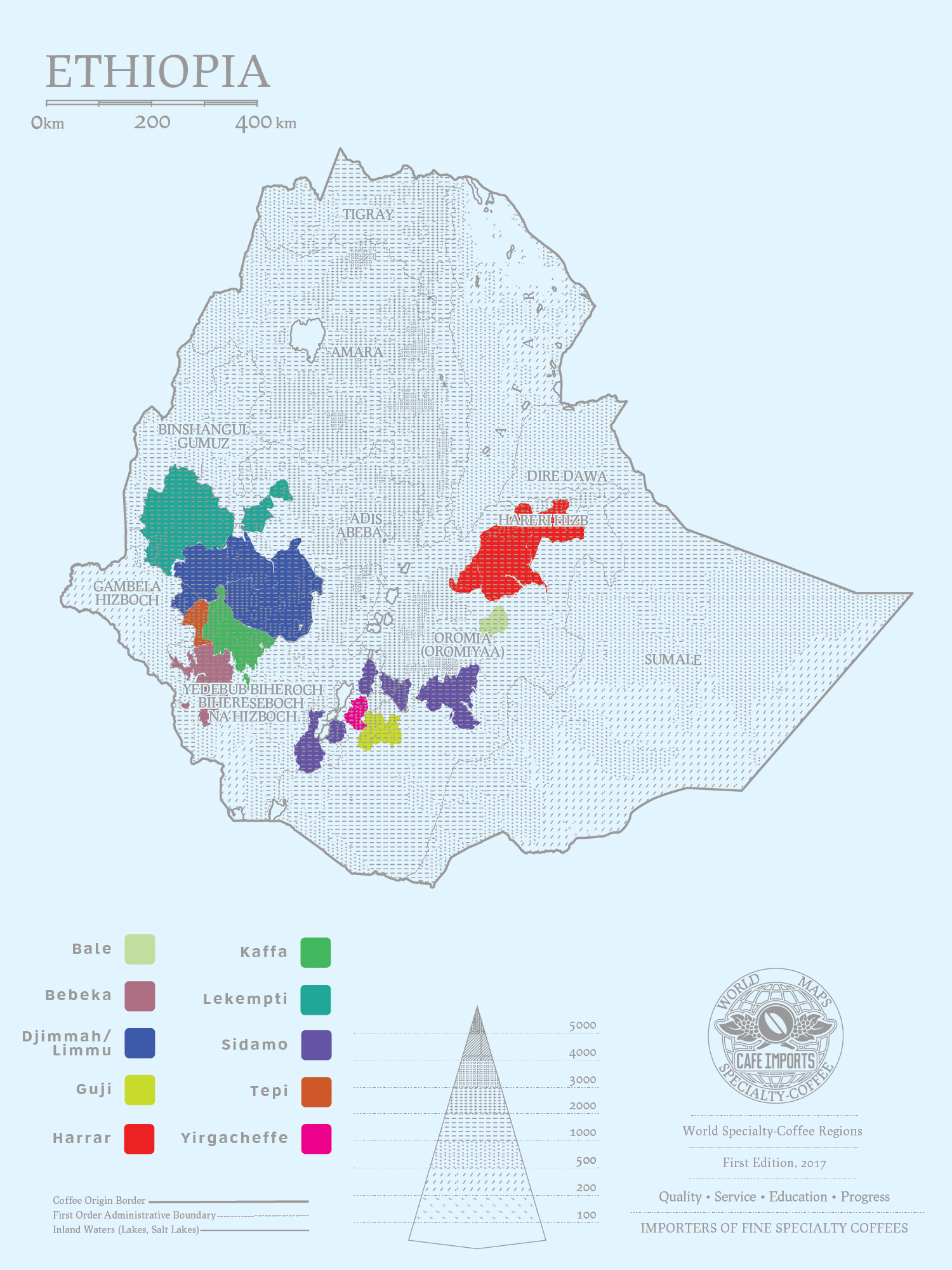

Jason Long, Café Imports’ CEO, has worked for many years to develop long-term partnerships in Ethiopia, and through our various relationships there, we are pleased to offer a variety of Ethiopian coffees every year. We buy directly from the second-tier co-operative society SCFCU (Sidama Coffee Farmers Cooperative Union), which allows us to bring Fair Trade– and organic-certified Sidama coffees from specific farmer co-ops to our customers. Through an export partner, we are also able to offer washing-station-specific lots, with limited traceability as purchased through the current ECX structure: In future years, the traceability of these lots should be increased, as we will be able to buy directly from the washing stations through our exporter. We also do offer some standard, less-expensive and less-traceable but still very good quality ECX lots, sourced for their quality and true-to-region profiles.

As the industry waits to see how the marketplace will develop in the wake of the Exchange changes, we are committed to strengthening our relationships, specifically in Sidama and within Yirgacheffe, and hope that coming years will see more farmer-specific lots and special-prep projects with price premiums attached for quality and differentiation.

HISTORY

Among coffee-producing countries, Ethiopia holds near-legendary status not only because it’s the “birthplace” of Arabica coffee, but also because it is simply unlike every other place in the coffee world. Unlike the vast majority of coffee-growing countries, the plant was not introduced as a cash crop through colonization. Instead, growing, processing, and drinking coffee is part of the everyday way of life, and has been for centuries, since the trees were discovered growing wild in forests and eventually cultivated for household use and commercial sale.

From an outsider’s perspective, this adds to the great complexity that makes Ethiopian coffee so hard to fully comprehend—culturally, politically, and economically as well as simply culinarily. Add to that the fact that the genetic diversity of the coffee here is unmatched globally—there is 99% more genetic material in Ethiopia’s coffee alone than in the entire rest of the world—and the result is a coffee lover’s dream: There are no coffees that are spoken of with the reverence or romance that Ethiopian coffees are.

One of the other unique aspects of Ethiopia’s coffee production is that domestic consumption is very high, because the beverage has such a significant role in the daily lives of Ethiopians: About half of the country’s 6.5-million-bag annual production is consumed at home, with roughly 3.5 million bags exported.

Coffee is still commonly enjoyed as part of a “ceremonial” preparation, a way of gathering family, friends, and associates around a table for conversation and community. The senior-most woman of the household will roast the coffee in a pan and grind it fresh before mixing it with hot water in a brewing pot called a jebena. She serves the strong liquid in small cups, then adds fresh boiling water to brew the coffee two more times. The process takes about an hour from start to finish, and is considered a regular show of hospitality and society.

The majority of Ethiopia’s farmers are smallholders and sustenance farmers, with less than 1 hectare of land apiece; in many cases it is almost more accurate to describe the harvests as “garden coffee,” as the trees do sometimes grow in more of a garden or forest environment than what we imagine fields of farmland to look like. There are some large privately owned estates, as well as co-operative society comprising a mix of small and more mid-size farms, but the average producer here grows relatively very little for commercial sale.

PROCESSING AND PROFILE

There are several ways coffee is prepared for market in Ethiopia. Large estates are privately owned and operated by hired labor; the coffee is often picked, processed, and milled on the property. On the other end of the spectrum, “garden coffee” is brought by a farmer in cherry form to the closest or most convenient washing station, where it is sold and blended with other farmers’ lots and processed according to the desires of the washing station. Co-op members will bring their cherry to be weighed and received at a co-op washing station, where there is more traceability to the producer level as per membership rosters of the co-operative.

The profile of Ethiopian coffees will vary based on a number of factors, including variety, process, and microregion. As a general rule of thumb, natural processed coffees will have much more pronounced fruit and deep chocolate tones, often with a bit of a winey characteristic and a syrupy body. Washed coffees will be lighter and have more pronounced acidity, though the individual characteristics will vary.

Harrar coffees are almost always processed naturally, or “dry,” and have a distinctly chocolate, nutty profile that reflects the somewhat more arid climate the coffee grows in.

Sidama is a large coffee-growing region in the south, and includes Guji and the famous Yirgacheffe.

Here is a very basic breakdown of what we look for in coffees from some of the microregions of Yirgacheffe, in the Sidama region.

ADADO: Delicate stone fruit with citrus and floral layers that create a nice balanced structure.

ARICHA: Complex and almost tropical, with a juicy fruit base and a sugary, floral sweetness.

BERITI: Prominent florals backed by a creamy citrus.

CHELCHELE: Cooked-sugar sweetness more like toffee or caramel, almond, and a floral, citrus overtone.

KOCHERE: Fruit tea backed by citrus and stone fruit.

KONGA: Peach and apricot—more floral stone fruit—along with a strong, tart citrus.

** About Ethiopian place names: There is much confusion and inconsistency where place names are concerned in Ethiopia, partially due to the fact that Amharic does not use a Roman alphabet like English does. Therefore, it is not necessarily incorrect to spell the region as Yirgacheffe, Yirgachefe, or even Yirga Chefe. We have chosen a company-wide set of standard spellings for clarity’s sake, but there are various ways of interpreting the phonetic spelling of certain places.

As for Sidamo vs. Sidama, it has been brought to our attention that “Sidamo” is a somewhat disparaging variant on the place name, and we have decided to use the more acceptable Sidama instead.

THE ETHIOPIAN COMMODITY EXCHANGE

The Ethiopian Commodity Exchange (ECX) was established by the Ethiopian government in 2008 with the intention of democratizing marketplace access to farmers growing beans, corn, coffee, and wheat, among other commodities. As farmers in Ethiopia typically own very small plots of land and are largely sustenance farmers—growing what crops they need for household use and selling the surplus for cash—it was decided that standardization would be the most egalitarian way to improve economic health and stability in the agricultural sector.

The ECX strove to eliminate the barriers to sale by giving farmers an open, public, and reliable market to which to sell their products for a set and relatively stable price. At its inception, the ECX rules dictated that any coffee not produced by a private estate or a co-operative society was required to be sold through the Exchange, which established guaranteed price and sale for farmers, but by design, it took the “specialty” out of the coffee and turned it into a commodity—escaping all traceability aside from the most basic regional and grade information.

Part of the definition of a “commodity” is that it must be replaceable: For instance, 100 bags of Grade 1 washed Yirgacheffe bought in December must be of equivalent quality to 100 bags of Grade 1 washed Yirgacheffe bought in August, period. Coffees are assigned grades based on their uniformity, cleanliness, and presence or absence of defect without consideration for flavor notes.

After pushback from the specialty-coffee industry and several rounds of intense negotiation, a later iteration established that washing-station information was made available after the coffees were purchased, though certainly tracing them down to the individual producers would prove impossible.

In March 2017, the ECX voted to allow direct sales of coffee from individual washing stations, which will not only allow for increased traceability, but will also allow for repeat purchases and relationship building all along the chain—a change that increases the potential for higher prices to the farmers. It remains to be seen what the impact of greater traceability and more direct sales will have on specialty coffees from Ethiopia, but the industry appears optimistic.